CONTENTS

- 0. Introduction

- Chapter 1: PERSON

- Chapter 2: LIFE

- Chapter 3: ENVIRONMENT

- Chapter 4: SOCIETY

- Chapter 5: CULTURE

- Chapter 6: COMMUNICATION

- Chapter 7: ACTIVITY SYSTEM

- Chapter 8: THE COGNITION SYSTEM

- Chapter 9: EDUCATION

- Chapter 10: WORK

- Chapter 11: MANAGEMENT

- Chapter 12: COOPERATION

- Chapter 13: CONCERNS

- Conclusion

CHAPTER 7: ACTIVITY SYSTEM

People’s actions form the activity system, in which each action also contains a reflection of all other actions.

Activity should never be the goal, but the means to achieve goals.

7.0. GENERAL CONCEPTS

Human life — at home, at school, at work, or anywhere else — consists of many actions. All these actions occurring in human life form the activity system.

It is not a qualification, structure, or law that operates, but a person as an individual, as a subject of self- and social management (but not as an object of someone else’s manipulation). Everyone can act alone, but success is achieved, as a rule, in cooperation.

All actions are elements of the activity system. Each element of this self-regulating system includes, to some extent, other elements of the activity system. For example, studying contains some work, creation, play, imitation, and other activities; and work, in turn, also consists in part of studying, creative work, play, and imitation. By considering only studies or work alone, it is impossible to gain credible knowledge of either one.

It should be clear that achieving a satisfactory level in any kind of activity presupposes knowledge of the system of the entire set of actions (as a whole).

7.1. ACTIONS

People work in factories, in the fields, on farms, in the forest, and at sea, but most of the members of society receive a salary for other kinds of activities. Most people work at home and in the garden as they rake leaves, wash dishes, etc. But where wages are paid, these same people perform much more complicated tasks than just work — managing, governing, networking, treating, training, etc. Training and providing medical care are not work but are processes that are many times more complicated than any work (the exception is perhaps the work of a bomb defuser). Playing sports is not work, but there are professions within which athletes work as players, runners, throwers, etc. Although, in principle, a game itself is not work, a game is a game.

The essential aspects of any action are:

- content and form;

- significance and meaning;

- rhythm and tension;

- feasibility, efficiency, and intensity;

- resources and conditions;

- opportunities and dangers;

- health and safety;

- overall security;

- direct and indirect connections and dependencies;

- results that can be assessed while considering their quantity, quality, and timing;

- consequences that must be anticipated in a timely manner, prevented from occurring, and compensated for;

- payment and/or other compensation.

The aim and goal of the subject (actor), as well as role and status, are significant.

There is learning (not coursework!) going on in school, in which there is very little work. Graduate students and doctoral students are not engaged in scientific work, they research and create, and there is virtually no work in research and creativity. People who attend meetings here and there are not engaged in public work, they are setting up public life in various spheres, regions, and levels of regulation.

MULTIPLE POINTS OF VIEW

It is impossible to achieve a satisfactory qualification by learning a single action. Consequently, the object of training must be the activity system.

The system of human activity has a complex structure. To discern it, it is necessary to observe a person over a long period of time in different conditions, circumstances, and situations; for example, how they behave in conflict and calm situations, in situations of choice or compulsion, in real and game situations (see 3.2.).

It is important to notice the dominant action (the action that is superior in its importance and significance to others). It is important to notice the level of risk, the creative tension, the danger. A scientist who discovers a fundamental regularity or even a law that they can write down on a napkin or the lid of a cigarette box (remember Einstein), deserves exceptional recognition, even though the result of their discovery cannot in principle be measured or adequately paid for. Only a few scientists receive the Nobel Prize or a similar award.

It is not customary for a scientist, artist, or composer to be paid for their work, although research and the creative process are also often accompanied by many simple and routine activities. They get paid for their creativity.

There are many points of view. In this book, we emphasize the importance of goal-oriented activity (see 2.10.). However, this does not mean that other activities, such as chaotic, situational, coercive, etc., could be neglected. To some extent, every more or less continuous action contains all of these types of actions.

Coercive actions are those in which there is no choice — they are obligatory. The more coercion, the less freedom of choice, the less opportunity to create, explore, think, and decide for yourself.

Coercive actions, of course, also allow you to perform some tasks and obligations, but instead of joy and synergy, there are consequences: fatigue, impatience, indifference, and apathy. That is, estrangement sets in, followed by alienation. It is important to remember that a person’s sense of responsibility and activeness is formed only through their independent decisions!

Often you can observe that people do what they like rather than what is necessary. It happens that all actions are directed at a single, highly visible and universally admired fragment, rather than at a system in the context of the various metasystems. However, only a systematic and comprehensive contemplation of systems can be considered satisfactory.

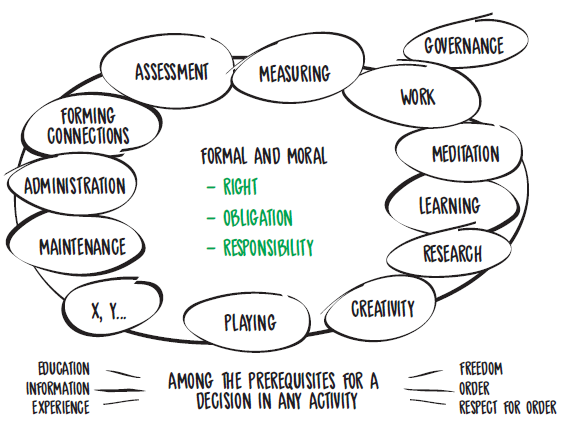

If a person is not aware of any important activity in a specific culture (study, work, creativity, play, etc., see Figure 7.1.1.), or they deliberately ignore it, they cannot be very good at any activity. Non-systematic actions can reach the level of an amateur, but it is impossible to reach great success.

A prerequisite for success in a group is the synergy formed as a result of complementarity and mutual attention, on the basis of which new ideas mature and people improve. At the same time, the group can encourage its members to go deeper, explore, study, create, and avoid mistakes — superficiality as well as occasional lapses and errors.

PLAYING AS ONE OF THE MAIN ACTIONS

Playing is not only one of the basic inherent human actions, but also a mechanism for the formation of personality. Playing is an extremely complex and substantial action. Most playing takes place in true situations rather than in game situations. If someone starts playing as if they are playing (pretend playing), it may well happen that they will be called out or expelled from the game. Playing is of fundamental importance in human life. Through playing, a person is socialized (see 2.2.).

Playing has an educational effect only in a true situation.

Through playing, a person discovers themself and others, creates, and builds relationships. Through playing, people can learn to get to know each other, to train the skill of quickly and easily changing roles, to represent themselves to others, to achieve the same results, to win and lose.

Birthdays, weddings, Midsummer Day, cotillions, song and dance festivals, and all customs, rituals, and traditions (see 5.1.) are also essentially games. Every game has its rules. Knowledge of the rules and the accuracy of their execution by participants helps to understand who is who. Playing allows you to test each other’s honor and sense of proportion, the ability to stay within certain boundaries, etc.

Playing (as well as other actions) contains all other elements of the activity system, including work.

ACTION IS NOT THE GOAL!

For a young child, as for an infantile adult, some action in itself may be a goal, but mostly the action is still a means to help achieve a goal. People who have had enough time to think about life understand that something big and significant can only be achieved through systematic activity. Therefore, a citizen should also define themself as the creator and custodian of the system. An action can become effective if a person manages to think of a system and act according to it.

The models of systematic thinking — barrels and anchor chains, with which Estonian sailors and farmers thought in the ancient days — have already been mentioned more than once in our book. Jokes are jokes, but both the “law of the barrel” and the “law of the anchor chain” are worth remembering in our day (see 1.0.).

7.2. LEVELS OF REGULATION

Society, in terms of its structure, is not a strictly hierarchical system. However, it has clearly defined levels of regulation and management, the specifics of which every citizen should understand.

Any problem has its own peculiarity at all levels of (self)regulation and management. No problem is solved at the same level where it manifests itself, nor are the causes of tensions solely at the level at which the flame flares up. To find satisfactory solutions, it will be advisable to act as in the famous children’s dance around the fire: two steps in, two steps out (steps up and down two levels). There are at least five levels of regulation and management to consider (See Figure 7.2.1.).

At the level of the individual, there is maximum freedom of choice and minimum uncertainty. On the societal level, the opposite is true: minimum freedom of choice and maximum uncertainty. In between are all the other levels of regulation, such as family, community, organizations, institutions, etc.

As the reader already knows (see 4.3.), the living environment is formed in the unity of horizontal and vertical regulation. There is an institutional level, agency level, and others, ending with the family level and the individual level. Keep in mind that each level has its own specifics.

For example, through vertical regulation entrusted to agencies, conditions should be achieved in which none of the prerequisites for the functioning, change, protection, and development of the state would be absent and worked against the intended ones, and connections in any of the vital spheres could not be ignored.

It is worth repeating that effectiveness is a function of systematicity! At all levels of regulation, management has (must have) the rights to fulfill (all!) its obligations to residents and the obligation to take full responsibility for the attendant direct and indirect results and consequences of these activities (or lack thereof). The people are not a means of achieving any goals by officials, etc. (whether it is the balance of the budget or something else); the goal is the well-being of the people, as well as the preservation of culture and all cultural values, including the native language.

ANY PROBLEM HAS DIFFERENT CONTENT AT EACH LEVEL OF REGULATION

The same problem at different levels of regulation has its own, different content from other levels. For example, consider transportation as a problem.

At the level of the individual, there is a choice: whether to go by bicycle, car, or public transportation? Where to park your car, where to repair it, etc.?

At the family level, the questions to decide are who goes where, who drives whom, at what time who should drive where? How to consider each other’s interests from a logistical point of view?

At the city and district level, transportation topics include roads, pipelines, bridges, tunnels, public transportation, taxis, traffic lights, crosswalks, bicycle lanes; in winter, snow removal is added to all of the above.

At the state level, it is necessary to monitor how road, rail, sea, and air transportation function; what is the condition of the road network; whether traffic schedules meet the needs; how to ensure safety; etc.

At the international level, it is customary to deal with maritime and air transportation safety, reducing environmental pollution, etc.

To understand transportation as a problem, it is not enough to navigate to any one level and deal only with what lies on the surface. It is necessary to talk about each level and what is happening at that level, and the citizen needs to see a cross-section of the problem. You can only be fully engaged in a field if you have the appropriate models.

For example, there are many offices with hundreds of architects, engineers, and other professionals to design buildings. In society, however, there is virtually no such design of the processes that take place. So-called politicians sometimes believe that all they need to do is to have power and show initiative, and everything else is secondary and optional.

7.3. PROFESSIONAL MODELS

The ability to grasp the whole picture cannot be formed by itself, randomly. The prerequisites for the formation of a professional (and simultaneously their tools) (see 1.7.) are models with which it is possible to see the whole, as well as the meaning of its parts, subsystems, and elements.

With the help of models, it becomes possible to describe things and their aggregates, phenomena, processes and their factors, as well as their dependencies and connections. Through models, it is possible to formulate as a problem the contradictions between the current and desired state of affairs and focus both on figuring out their causes and on creating a system of necessary measures to reduce and eliminate them.

MODEL AND MODELING

A model is an object that characterizes (represents) another, more complex object and corresponds proportionately to it.

A model can be a:

- textbook;

- prerequisite of scientific research;

- prediction;

- scenario;

- argument.

The meaning of a model is shaped by the context.

A professional deals with the system, an amateur deals with one part of it, and a layman just says it would be nice to deal with it.

Modeling is a method of cognition, fixation, preservation, and transmission of existing or represented objects, phenomena, processes, connections, and dependencies.

Modeling consists of constructing and using models.

Modeling is a modern:

- research method;

- creative method;

- learning method (method of teaching and studying);

- consultation method;

- playing method;

- work method;

- management method, a method of administering, networking, governing, and organizing other goal-oriented processes.

WHO NEEDS MODELS?

Models are needed by those who are gifted with:

- a true and abiding interest in cognition;

- a desire to teach something or learn something;

- a need for understanding and comprehension;

- an obligation to be responsible for their activities and their final results.

Profane people, dilettantes (see 1.7.), and posers do not need models.

A model can represent the form and content of thought or their unity; a thing, phenomenon, process, or their parts; subsystems, elements and their properties; the creator, user, and assessor of the model; environment, alternatives, etc.

- Development (qualitative transitions) can be facilitated if all the factors essential for development can be ensured.

- Efficiency is a function of systematicity.

In a formal sense, a model encompasses the form and structure of the phenomenon, process, or subject under consideration, as well as the actions, rules, principles, and methods of research or study. In this case, the form and content of a model may differ significantly from the modeled object, process, or phenomenon.

A model cannot be identical to the object on which it is based. The value of a model is simplicity, but not the kind of simplicity that can make you lose the main thing.

A model presents (should present) such characteristics, connections, and dependencies that, in the opinion of the model’s author, should be noticed, recognized, understood, accepted as essential, formulated, connected, justified, and taken into account by others.

If we classify models based on their cognitive and theoretical nature, we can distinguish heuristic and didactic models (designed to search or learn). When classifying based on the relationship between the original and the model, there are analog, mathematical, geometric, etc. models.

MODELS THAT GIVE AN IDEA OF SOCIETY

Models describing social phenomena and processes characterize:

- conditions, circumstances, and situations: that is, the environment in which people find themselves;

- events occurring in their time, advertising and propaganda, different kinds of interpretations; political, ideological, economic forecasts and illusions; the compilers themselves, including their development, interests and claims, hopes and fears, degree of freedom, ambitions, alternative ways of thinking, etc.

In most cases, models can more effectively and qualitatively convey interpretation, encourage people to explore and discover systems and metasystems as well as their connections and dependencies, causes and consequences; to arouse interest and achieve its satisfaction.

With the help of models, it is sometimes possible to avoid the desire to give up on everything, which arises when one encounters thoughts that seem impossibly difficult at first.

If knowledge is transmitted as a model, it becomes easier to use it as a tool of cognition (instrumental value) — that is, so that it is easier to understand complex terms, rules, laws, formulas, their occurrence and impact; to discover and weave a system of causes and connections of events, their results and consequences. With the help of models, it is sometimes possible to avoid the quickly arising desire to give up on everything, which appears when you encounter thoughts that seem impossibly difficult at first.

Making models contributes to learning the logic of their construction, as well as supporting independence and the development of the thought process. With the help of a model, any abstraction acquires a form, structure, and content that are understandable and accessible for discussion.

- A fact is an indisputable truth; it is something that really happened, was happening, or is happening.

- In order for statistical facts to become meaningful, to turn them into information, it is necessary to interpret them within the framework of appropriate theories.

- The meaning of each fact is formed in context. Any fact can be interpreted in several contexts.

A democratic polity in our time is not possible without social research and a management that clearly understands what real research is, under what conditions it can be conducted, what can be discovered through it, what is a fact, and what characterizes the validity, representativeness, and systematicity of facts (see 8.2.).

To form big decisions in society, it is necessary to have information about:

- the structure of the population, how people live, what they enjoy, what they expect, what they hope for, what they love, what and whom (and why) they fear or despise, what they feel elated about or try to escape from;

- what people from different categories of society are trying to achieve, what the actual results and consequences are;

- how to use the results of scientific research.

7.4. MODELING ACTIVITIES

Theories (models of thought) are necessary for any more or less carefully planned activity. In more complex cases, it is reasonable to find multiple points of view to consider the object of interpretation (person, organization, thing, activity, phenomenon, process). Then you should take a piece of paper and write down, if possible, everything that characterizes this object, see what it depends on, and what, in turn, depends on it (see Figure 0.3.2.).

- Everyone can practice and learn how to make models.

- You should start by modeling those things, actions, phenomena, or processes with which you are more familiar and which are not too difficult for you.

This book takes a closer look at some elements of the activity system — work (see 10.) and management (see 11.), learning (see 9.1.), teaching (see 9. and Figures 11.1.1. through 11.1.8.), administering and forming connections (see 2.9.). We should not conclude from this that we consider other actions to be less significant and think it possible not to know or consider them. What little is revealed here should serve as an example for a further search.

Then everyone will think independently, starting with modeling familiar and simple actions, gradually moving on to more complex and obscure actions.

It is important that each action be seen as a phenomenon (statically) and as a process (dynamically). Statically, any action can be viewed as an n-dimensional space, and dynamically, as a temporal sequence and logical connection of a continuous chain of events.

With the help of models, any action can be considered as a problem.

Through a model, it is possible to clarify what is already sufficiently clear and what is not yet very clear, what can continue to be done the old way and what needs to be changed, what can be handled alone and what should be a combined effort, etc.

Professionals (see 1.7.) think systematically and have classifications. The dilettante has incomplete knowledge, and often the little they have accumulated in their head is also mixed up.

Only ordered knowledge is of value. Knowledge that one knows how to use, whose meaning and significance one understands because one imagines the relevant general, intermediate, and concrete theories, has value.

Every action must be seen both statically and dynamically (as a phenomenon and as a process), otherwise it will not be possible to understand its essence.

Theories are needed to make more or less satisfactory models. It is quite possible that some readers will be able to find, in books, models that have already been compiled on the basis of various actions. If you do not succeed, you will have to create them yourself.

Each field of activity has its own specifics, and in accordance with it, some principles should be taken into account. In the preparation of models, both a methodology (a system of principles) and a system of goals and means are necessary. In practice, models (theories) acquire value together with methodology and methods (see 8.3.).