CONTENTS

- 0. Introduction

- Chapter 1: PERSON

- Chapter 2: LIFE

- Chapter 3: ENVIRONMENT

- Chapter 4: SOCIETY

- Chapter 5: CULTURE

- Chapter 6: COMMUNICATION

- Chapter 7: ACTIVITY SYSTEM

- Chapter 8: THE COGNITION SYSTEM

- Chapter 9: EDUCATION

- Chapter 10: WORK

- Chapter 11: MANAGEMENT

- Chapter 12: COOPERATION

- Chapter 13: CONCERNS

- Conclusion

CHAPTER 11: MANAGEMENT

Management itself is difficult. It is much less difficult to manage compared to achieving self-regulation of the system, that is, no need for management.

A citizen should possess the ability both to manage and to avoid management.

11.0. GENERAL CONCEPTS

Sometimes a person has difficulty because they do not quite understand what is being talked about. The words “management”, “governance”, and “administration” (and other words that denote actions with a definite aim and goal) have many meanings, sometimes radically different from each other. At each level of regulation and management (see Figure 7.2.1.), it is necessary to know all these actions together with a second component that makes them meaningful. Management makes sense in conjunction with execution, governance makes sense in conjunction with subordination, administration makes sense in conjunction with maintenance, etc. (see Figure 2.9.1.)

A citizen who wants to navigate in management and other goaloriented systems must start with the people, or rather, with themself. If this succeeds, the desire to achieve such an interaction and relationship with other subjects will form as an aim, which virtues will be sufficient for regulating. In this case, managers should deal with the living environment and the future, avoiding, if possible, direct management. In order to achieve such a level, you must be a generalist (see 1.7.).

It is important that the processes proceed in a suitable direction, expediently, and at an acceptable pace. The hardest part is determining which direction is right in every sense and which action is expedient enough. As a rule, efficiency is usually a particular concern. But the value should still be considered the unity of efficiency, intensity, and expediency.

It also happens in society that something, which publicly seems very positive here and now, might occur disastrously in the long term or on a global level (see Figure 9.5.1.).

Society is not homogeneous. What is admirable to some may be unacceptable to others. Many people are afraid of change because they are afraid of the unknown possible consequences.

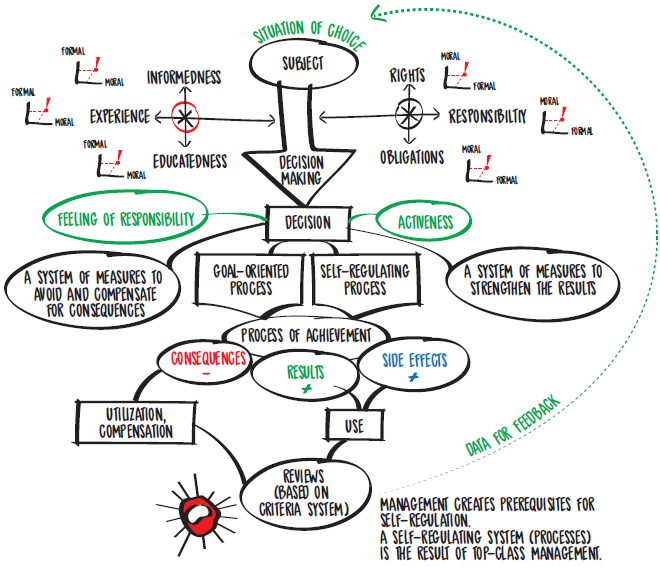

In order to make sense of management, everything on which management and self-regulation depend, as well as everything that depends on them, should be identified, if possible (see also Figure 0.3.2.).

- Through goal-oriented activity and learning, one must come to understand the primacy of self-regulation.

- Management competency is needed primarily to avoid management; it is also necessary when you need to adjust something, start or stop something, or try something new.

It is also necessary to come to the understanding that self-regulation is primary and management is secondary. To achieve this level, satisfactory occupational preparation is needed, which at the moment is not provided by schools.

The object of management is processes. Only a small portion of processes are goal-oriented and manageable. The subject of management is a person or set of people who have the right to decide. In a normal case, the subject of management is also endowed with responsibility for the direct and indirect results and consequences of all their actions — for the functioning, change, and development, as well as the prerequisites for the development of a person, environment, and organization.

It is important to remember that only self-regulating systems can develop. Management, governance, administration, etc. (see Figure 2.9.1.), are necessary only when self-regulation is not functioning, or is functioning in the wrong direction, intermittently, ineffectively, dangerously. The need for management may also arise when the system has lost vitality and is no longer able to continue functioning independently. If internal and external tensions have grown to dangerous proportions, and the system lacks the capacity to discover the causes of decay, it is not — as was already known in ancient Rome — necessary to reinforce order, but to expand the boundaries of freedom.

MANAGEMENT, EXECUTION, DECISION-MAKING

People endowed with the right to manage something have at the same time the obligation to execute something. Everyone must be responsible for the results and consequences of both management and execution.

A person can behave like a citizen if they have satisfactory training in both management and execution, not just one thing!

A sense of responsibility and activeness is fostered through participation in making decisions — no other way is known!

People will be able to comprehend the life of society and behave like citizens (vt 1.6. ja joonis 2.9.1.) only if they come to the understanding that:

- management is meaningless without execution;

- only pre-made decisions could be executed;

- decision-making lies in the center of management;

- when making a decision, the main issue is not the decision itself, but everything that goes along with it;

- decision-making (NB! not playing at decision-making), in addition to the decision itself, is accompanied by a sense of responsibility and activeness of the people who took part in making the decision;

- all people are in some connections decision-makers and at the same time the executors;

- people should execute both their own decisions and the decisions of others (received from others as obligations or tasks);

- people do not gain recognition and climb the career ladder through management, but as executors;

- consequently, all people who wish to productively self-actualize and contribute to the prosperity of their state, native land, institution, enterprise, organization, etc., need preparation in both management and execution.

Management can be assessed both on the basis of a chain of actions and on the basis of direct and indirect results, as well as consequences. The living environment and hidden/public codependencies are also important.

- Functions exist and accompany any activity, regardless of the subject’s desire.

- Principles (agreed-upon conditions) are prospective (forward-looking).

- Criteria (basis of assessment) are retrospective (focused on the past).

- Prerogatives are rights that could not be delegated.

Behind the system of management functions (objective co-dependencies), you can see its essence. Quality, that is, the visible side (appearance) of management, is manifested in the extent to which it meets the consumer’s expectations and corresponds to the stereotypes formed in the culture, established standards and ideals, and the likely future needs.

WHO IS SUITABLE FOR THE MANAGER ROLE?

Here is a long list, so that the reader has a solid basis for reflection.

A subject is suitable for the role of a manager if they:

- know the starting point (location or state in n-dimensional space before the planned activity);

- imagine what they want to achieve, where they want to go and what they want to be, what circumstances, conditions, and situation they want to create;

- represent the expedient direction (aim) and the object of management (process) as a path from a starting point to a destination (state of being), as a successive chain of stages and transitions (see Figures 0.3.3. and 0.3.4.);

- imagine the living environment in which it will be necessary to act along this way (see Figure 3.0.1.);

- are capable of creating, obtaining, and preserving the means (system of means) necessary to maintain the aim and achieve the goal, including resources and the conditions necessary for their use;

- NB! If any of the necessary resources are missing, there is no corresponding condition for using other resources. For this reason, the process is either interrupted or dramatically slowed down and/or made more costly because the missing (too weak) resource must somehow be compensated for. Somehow or other you can compensate for everything for a while, but you cannot compensate for everything all the time.

All self-regulating systems that one tries to manage, despite the fact that management does not have the ability to think and act systematically, either wither or perish.

- are in a position to establish a system of principles of activity, content, form, and adherence, which forms the culture of the organization;

- are able to establish criteria for assessing environments, executors, activities, results and consequences, knowledge, and attention that ensures fair business conduct and fair vertical relationships;

- are able to establish a connection that provides mutual opportunity to be promptly and systematically informed, to feel involved;

- are capable of goal visualization, that is, to ensure that the “output” of each stage is suitable for the beginning of the next stage, and the “output” of each process (result) for the following processes (for all those processes to which it should be suitable);

- are in a position to provide feedback on their own activities and the activities of others, which means:

- collecting data on each stage and the process as a whole, as well as their results and consequences,

- interpreting these data (transforming them into information),

- assessing both activities and executors, the environment, results and consequences,

- making conclusions and paying attention to them in future activities;

- are able to set priorities (identify key factors and form a sequence of actions);

- are able to create the necessary prerequisites for cooperation, including clarifying the sphere of responsibility, specific responsibilities and subordination, rights and obligations, accountability, foundations of creativity, research, careers, etc.;

- are able to establish prerogatives (designate the areas of their own exclusive rights, decisions, and responsibilities);

- are able to create a system for preserving all that must not be altered, that must be cherished, protected, and strengthened;

- are able to create a system for fairly rapidly introducing changes to everything that has become unusable (obsolete morally and physically);

- are able to provide as perfect an infrastructure as possible, bearing in mind that efficiency is a function of infrastructure, and that only infrastructure that is considered holistic by modern standards can be called satisfactory;

- are able to take into account that the success of organizations and institutions depends primarily on staff — the unity of people’s cultural and social connections, motivation, orientation, qualifications, erudition, intuition, affiliation, etc. (see 9.3.), and ability and willingness to cooperate;

- know that only systematic activity can be satisfactory.

- Efficiency is a function of infrastructure.

- Only infrastructure that is consid-ered (by today’s standards) holistic and corresponds to real needs can be called satisfactory.

11.1. THE SUBJECT AND OBJECT OF MANAGEMENT

The subject of management can be an individual or a set of individuals with adequate self-knowledge and self-awareness (I); group cognition and consciousness (we); cultural cognition and consciousness (identity); social cognition and consciousness (civic sense). Of course, decision makers must always bear formal and moral responsibility and have the accompanying formal and moral rights necessary to fulfill their obligations. Here we can talk separately about rights and obligations, as well as responsibilities, but in life they all function together and simultaneously. If at least one (any) of these components is missing or is not strong enough, then the other two lose their meaning.

The subject of management is an individual or set of individuals acting together, making decisions and bearing responsibility, and as well as possessing:

- adequate self-knowledge and self-awareness;

- group cognition and consciousness;

- cultural cognition and consciousness;

- social cognition and consciousness;

- modern occupational preparation;

- orientation, enabling them to act both as the maker and as the executor of decisions;

- a willingness to keep learning (not play at learning!);

- an understanding of the overarching task (see 2.12).

The subject of management is an individual or group of individuals who has the right to decide, organizes the execution of decisions, and is responsible for the result and consequences. Management as an action hides an eternal dilemma. If all the people affected by a decision were to participate in making it, it would be impossible to say who made the final decision, and the responsibility would have to be shared by all. In fact, then no one would be responsible for anything. If the manager (director, minister, etc.) alone decides for everyone, then they must be solely responsible for everything in the same way. In practice, this is impossible. It should be clarified each time separately where the boundary is and what the measures of delegation are. A similar dilemma is found in other goal-oriented processes.

INVOLVEMENT IS KEY

A key issue is the meaningful involvement of the community (the organization’s entire staff) in the processes that lead to change.

- First, it is necessary to achieve a satisfactory awareness among many (all) not of the innovation itself (see 11.3.), but of the circumstances and conditions that have formed, as well as the expediency and even inevitability of these changes. To do this, it is necessary to provide everyone with data from which they could understand the meaning of the accumulating contradictions. In order to convince people of the need for updates, an effective argument can be the forecasts, as well as scenarios based on them, for the near and distant future. If the staff fails to understand the need for updates and the possible consequences of tolerating contradictions, then the smooth development of innovation will be in jeopardy.

It is not worth it to intimidate people or, on the contrary, appeal to them with sweet speeches. They should be presented a fairly holistic picture, not just bare numbers or information taken out of context. It is necessary to give the opportunity to be informed not only about the current terms and conditions, but to explain honestly why these circumstances existed and what (what condition) should have been achieved through innovation.

MAIN PROCESS AND SIDE ACTIVITY

What would be adviseble to do? To begin with, you should model the terms and conditions both statically and dynamically. Then you can compare the present with both the past and the future, and formulate the contradictions as problems that form the need for innovation. After that, it will be possible to explain the current conditions here and elsewhere, show the directions of changes and the intensity of the change. It is necessary to come to the point that we have formed and preserved faith in our own strength, as well as the knowledge that we ourselves must cope with the causes of our problems. It is necessary to conduct an analysis in order to quickly discover the causes of problems and other connections with a systematicity considered satisfactory. As a rule, this can only be done by people who have achieved the appropriate preparation.

If direct and indirect, public and hidden, local and global causes of problems could be discovered, a system built from them, and then made public, it will be possible to generalize, make assessments, and draw reasonable conclusions.

When engaged in the main process, you should think about:

- how to draw attention in a delicate enough form to what in any case needs to be treated with care and protected;

- how to make alternative decisions (with their pros and cons);

- how to support, defend, and inspire those who are in search of alternative decisions, new arguments, and counterarguments;

- how to help prepare staff for all stages of the upcoming innovation;

- how to keep staff and, if necessary, the general public informed about how the innovation process is going;

- how to provide support and encouragement to those who find themselves in a difficult position because of the innovation;

- how to recognize those who are particularly diligent and passionate about the innovation;

- how to draw up a comprehensive conclusion reflecting the process as a whole, give assessments, and make conclusions for the future.

Thus, the question is not only what the best path to a decision looks like, but how to make sure that the people effected by the decision are competent enough to participate in designing and making those decisions.

Above all, it is important to ensure that the people effected by the decision have the competency to participate in designing and making those decisions.

If management has more or less satisfactory specialty preparation, but lacks professional and occupational preparation, it can happen that the quality of decisions will be weak, professionals will seem to be a hindrance, and accountability will be out of the question.

THE GREATEST SUCCESS COULD BE ACHIEVED BY TEAMS

It is assumed that the subject of self- and social governance has the preparedness for orientation, independent decisions, execution, making connections, analysis and correction, is able to actually put all these skills into practice, be responsible for the actual and possible consequences of their own actions (see Figure 1.4.1.). Preparedness alone is not enough, but activities without preparation will not lead to anything good.

Of course, sometimes you can achieve success individually, but the greatest success is achieved by teams that have a spirit of mutual trust and cooperation (see 12), care, and respect. People are inspired by synergy. Particularly fruitful and admirable are those communities where order prevails, ensuring that all are free and able to create and preserve spiritual wealth. The value is the unity of freedom, order, and security. If one of the components is missing, the rest are meaningless!

In order to manage, the subject of management must possess the process and/or system of processes through which they would like to achieve some kind of results. To manage, one must know what facilitates and what hinders success, as well as have an idea of what can accompany management.

Much of what is discussed here for the goal of understanding management and execution is universal. Each person can think for themself how it would be wiser to act in the context of other goal-oriented actions (see 2.10.). In any case, it is necessary to orient, decide, implement, find connections, assess results and consequences, and (if necessary) to correct the activities carried out, including providing goal visualization and feedback (see 6.2.). It is important to remember that making decisions, as well as the lack of decisions, in addition to responsibility, is accompanied (may be accompanied, or may even be destroyed) by trust, faith, respect, hope, love, balance, etc.

SELF-REGULATION AND CONTINUITY

It is indeed difficult and important to manage, but it is even more difficult and much more important to achieve conditions in which there is no need for management and the processes are self-regulating. To achieve this level, management itself, as well as the communication and relationships of those involved in the management process, must be in good shape.

The prerequisites of management and self-regulation are:

- a comprehensive understanding of the problems and their causes;

- awareness of the meaning of problems at different levels of regulation and in different contexts;

- having forecasts;

- setting an aim and goals;

- obtaining means (resources and the conditions necessary for their use);

- setting the principles of activity;

- creating clear goal visualization;

- achieving interconnectedness;

- creating a system of assessment criteria;

- feedback;

- public reporting;

- preserving the spirit of cooperation and the capacity for creativity (including the prerequisites for synergy).

LEADER AND LEADING EMPLOYEE

A leader is someone who is considered as such, and a leading employee (civil servant) is appointed, named, and announced. Leader is an informal status, leading employee is formal. In a good case, a leading employee is considered a leader.

Each leading employee, as well as each leader and executor, has many roles (see 1.5.) The more likely a person is to succeed in life, the more roles they are good at, the easier they change and understand those roles, and the better they take into account their partners’ roles.

A leader’s reputation and success depends not only, and not primarily, on what roles they act in, but on how well they do in their roles. Assessment also depends on expectations and hopes; assessments and beliefs of colleagues, friends, acquaintances, and family; and the extent to which others understand the leader’s sorrows and joys in the context of various roles.

- Leader is an informal status, leading employee is formal.

- In a good case, a leading employee is considered a leader.

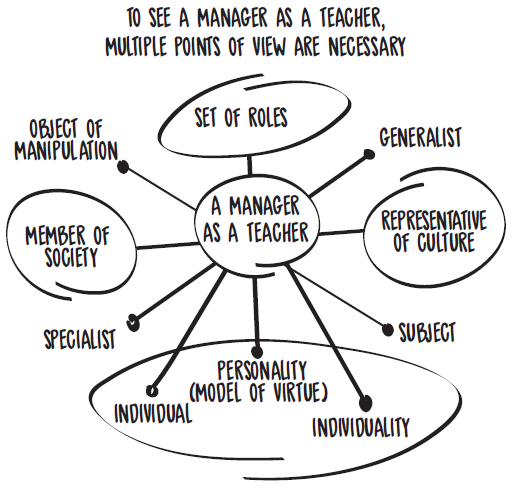

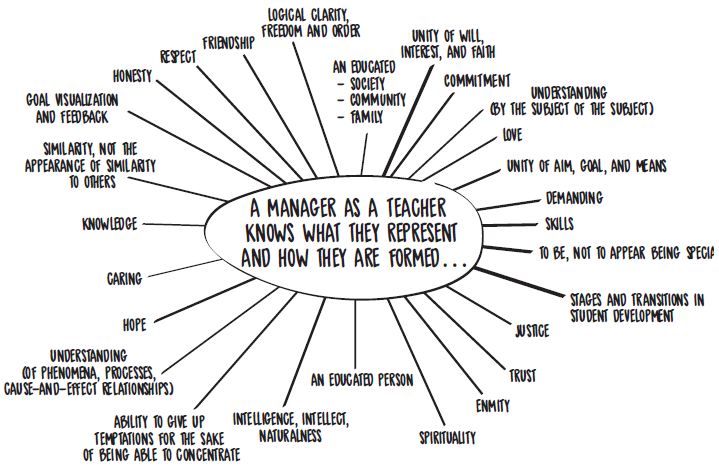

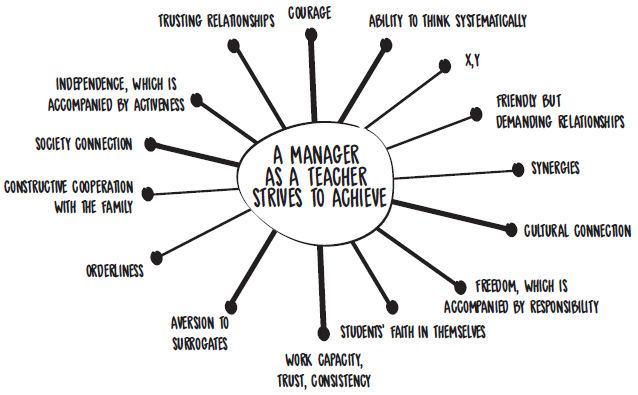

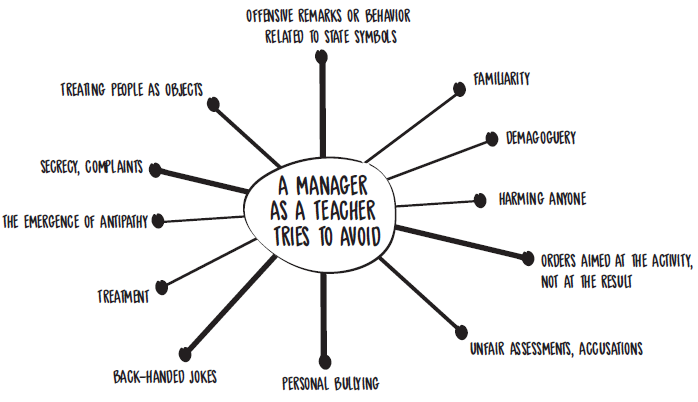

A person in a leading employee occupation, like it or not, is the center of increased attention. The public observes them as a generator of ideas and professional, analyst and decision-maker, inspirer, example to others, fighter, advocate for their people, mentor-teacher (see Figures 11.1.2.-11.1.8.).

Behavior in the context of different roles, in turn, determines whether a person wants to (and can) be a leader, or whether they are only a leading employee. Regardless of occupations, power, money, etc., a person is both their parents’ child and, in most cases, a spouse and parent in their own family. Almost everyone also acts as a friend and colleague. It is important not to confuse the roles of a friend and a holder of an occupation. As part of the occupational relationship, it is wise to keep some distance, so that there is no conflict of interest or reason to think about “how to fire a friend.”

The status of a citizen and the accompanying roles deserve emphasis. Authority is formed from the symbiosis of statuses developed in the context of roles. Authority is like a mirror. It takes a lot of time and effort, consistency, honesty, and hard work to create and polish it. Just as a mirror that has shattered into shards cannot be restored, neither can lost authority.

Reputation is shaped by many factors. Both personal and role factors, humanity, politeness, manners, clothing, expediency of professional activity, prosperity, etc., have significance. Especially important is the ability to listen and speak, faithfulness to the word, consistency, fairness. An indication of the prudence of senior managers and leading employees is basically the principle of selecting the closest circle of employees. Wise leaders invite those who are better at something than the leader is themself. Wise leaders are happy to organize seminars and actively participating in various types of learning. Wise leaders do not confuse opinion and knowledge. They present their assertions in conjunction with their reasoning and assume that others behave in the same way.

We present here a number of figures dedicated to the manager (ideally leader, not only leading employee) as a teacher (see Figures 11.1.1.-11.1.8.). Most of them look at the competency of the manager as a teacher. By managers, we mean not only directors, but all managers (decision makers) in all areas of life. The content of the pictures presented also applies to all teachers — working in schools, kindergartens, or anywhere else.

WHO IS CONSIDERED A LEADER?

A manager is considered a leader if they are a dedicated person who wants to be and is a true leader (rather than playing one!), serving as an example of self-actualization. They are trustworthy, loyal, honest and fair, caring, attentive and professional — a specialist in some field and, of course, a generalist. The profane or dilettantes are not considered leaders (see also 1.7.).

- A specialist is a highly skilled worker (executor).

- At the head of large organi-zations (as well as any large system), successful generalists are creative and established practitioners who are considered “one of us” by staff, but who are superior in almost every way to the rest.

A manager is considered a leader if they:

- do not give orders and commands, do not dictate how one should live and be, do not criticize and lose their temper, do not whine, but help to notice opportunities and dangers, causes and consequences, clarify tasks and obligations, goals and means, systems of principles and criteria;

- believe in themself and their teammates, in the meaningfulness of common activity, in the future, etc.;

- value naturalness, honesty, loyalty, and hard work;

- do not tell outsiders what happened to this or that colleague, and do not discuss their weaknesses in public, but defend and praise their colleagues, inspire them to research, be creative, search for optimal solutions;

- are the same as the others, but more punctual, more confident, more diligent, bolder;

- do not attribute to themself the achievements of colleagues, do not seek personal gain at the expense of others’ success;

- do not say or believe that they are the main one succeeding, and the rest only help as much as they can;

- prefer the role of a listener in discussions;

- speak only when they have something to say;

- criticize (if they criticize) the views, ideas, proposals, conclusions, etc., but not those who represent them;

- consider colleagues capable and hardworking, developing, succeeding and avoiding mistakes, complementing and enriching each other, acting as a team;

- inspire others to apply themselves, to make an effort, to continually learn, to explore, to create.

A leader values in colleagues independence, self-criticism, a sense of confidence, creativity, friendship, and mutual demand. Leading employees, on the contrary, usually value in people obedience, humility, subservience, agreement with the opinion of superiors, accuracy (punctuality) in executing orders.

A leader is a teacher and educator to colleagues, primarily by personal example. The prerequisites for success are sincerity and naturalness of intercommunication, faith in each other, trust, and respect.

A leader and a leading employee are formed in different ways: a leader in the context of culture (informal relationships), a leading employee in the context of society (formal relationships). It is valuable when both of these roles are combined in one person.

We have accumulated many observations over several decades, which now allow us to augment the characteristics of a true leader with the following formulations:

- they are able to consider people’s spirituality as of the highest value, while setting themself as an example in caring for humans, culture, and nature;

- they say what they think and do what they say;

- they think before speaking and do not talk about things they do not know;

- they are willing and able to connect theory, methodology, methods, and practice into one whole;

- they are able to see, recognize, and consider both cultural and social connections;

- they use public power only in the public interest and on the basis of the law;

- they want to serve the people, not the other way around;

- they understand that people and organizations can only be helped by something that gives them the opportunity to gain greater autonomy;

- they make sure that their activities are in accordance with the Constitution as well as good customs and rituals;

- they understand that the appointment, election, invitation to an occupation comes with only a formal right to participate in making decisions. To truly participate in making decisions, a moral right is also required.

- Appointment, election, invitation to an occupation comes with only a formal right to act.

- The use of a formal right requires a moral right!

Below are some details that also determine the level/status of the manager as a leader (or leading employee). What matters is whether they understand that:

- always and in every case the one who decides is responsible;

- it is reasonable to make decisions oneself only when others cannot (are not entitled to) make decisions;

- it is better to spend an hour helping colleagues complete a task or obligation on their own than it is to do it all for them in one minute;

- knowledge, opinions, and beliefs are valuable assets, but they must not be confused with one another or presented to others mixed up;

- competency is formed in a practical activity that combines all three components of preparation: by specialty, by profession, and by occupation;

- correct, forward-looking decisions are rarely popular;

- unsystematic interpretations and decisions are weak or wrong;

- speeches and decisions invented only to win the sympathy of the staff or the people have a boomerang effect, coming back to punish the very author;

- democracy is a function of culture and education (objective codependency), but it is cumbersome and expensive;

- the saying “God will give you an occupation, and the mind will follow” does not work.

A good manager (in the eyes of others as a leader) understands that it is not appropriate to consider and call themself a professional in matters about which they do not have the qualifications to judge. They understand that vanity, arrogance, hubris, etc. cannot serve as a guide for someone who wants to be a leader, and know that very good execution of weak decisions will only make things worse. If they do not have enough strength themself, then it is cheaper to invite an adviser or experts instead of postponing decisions, and hiding unsuccessful decisions or endlessly revising.

The more people who get involved in the discussion, and the more they themselves see that they are being listened to and considered, the better. Consequently, a manager as a leader needs to engage in public education in the broadest sense of the word.

UNJUSTIFIED AND JUSTIFIED STRUCTURES OF AUTHORITY

A person who has achieved a status due to their abilities, intelligence, diligence, consistency and many of the qualities mentioned above has justified authority.

Here we will pause briefly and look back 30-40 years ago, when an attempt was made to create a system in Estonia in order to increase the authority of management. Under this system, a person could only be appointed to a public managerial position with personal and behavioral prerequisites if they had at least four years of (successful) management practice and had completed at least six months of occupational training. In addition, directors and their deputies (all upper management), as well as middle management, were obliged to take advanced training courses every four years. The courses for upper management lasted two months, and were one and a half months for middle management. At the end of the courses, it was necessary to pass tests and an exam and defend independent research in front of a commission.

- A person’s authority is jus-tified if they have achieved the status because of their ability, intelligence, diligence, and consistency.

- Authority is unjustified when a person is placed in a position through fraudulent schemes, influential acquaintances, or hidden arrangements, without regard for their real knowledge, skills, and abilities, as well as personality characteristics.

- An unjustified authority structure leads to violating openness and causes uncertainty, which negatively affects both social and cultural connections.

An advanced training system, among other things, was under development. In the first half of the 1980s, so-called advanced training institutes were created in virtually all spheres of activity. In 19791988, the Institute for Advanced Training of Managers and Executives of the National Economy of the Estonian SSR (abbreviated JKI) was in operation. In 19891992, the same institution operated under the name Estonian Institute for Advanced Training of Executives. Medical, educational, agricultural workers, etc., had their own training centers. The occupational competency requirement was repealed in 1992.

People who had passed through the Tallinn JKI and the Department of Advanced Training of School Principals at Tallinn Pedagogical University (popularly known as the Lasnamäe Academy) helped to form such a communication space in Estonia that the conditions of the economic sovereignty program were formulated in an understandable way for the public. Every year, about 600 people who held senior positions in organizations of the economic sphere passed through the institute of advanced training. The ideals of independence were then ignited by universal enthusiasm.

There is no doubt that the people who took two or three 2- or 1.5month courses at the Institute for Advanced Training had a significant impact on the events of the 1980s. Communist party functionaries did not participate in such advanced training courses, and the difference between the intellectual level of administration workers and party officials grew to the point that the latter became an object of ridicule.

The level was far from professional in the Estonian economy of the time, but the instructors did their best to remedy the situation. They also tried to achieve implementing the principle of competency in the selection of managerial staff for various enterprises and organizations. In order to understand the context of these days — during the Soviet regime, all enterprises, land, and production means were state owned. There were two systems for career: communist party line or specialist line.

In today’s Estonia, there is no system for forming and maintaining a justified structure of authorities, which means that citizens should pay close attention to this.

Usually, a person who has unjustifiably gotten into an occupation is not so stupid as not to understand what they do not understand. The person is well aware of the shamefulness of the situation, and therefore begins to do everything possible so that this flaw goes unnoticed, and everything would look exactly the opposite. They begin to hide their actions, the reasons for their actions, and, of course, their failures, true self, level of preparation, etc.

If everything can be kept secret, then they begin to get rid of professionals and replace them with their own kind of people or with even stupider ones. Their style usually spreads, expands, and deepens very quickly. Education becomes unnecessary, teachers become extraneous, scientific research begins to seem like a waste of means.

COMPETENCY PRINCIPLE

It is up to the citizen to monitor compliance with the principle of competency in all spheres of life, at every level, and in every region. Care must be taken to ensure that only those with the necessary preparation for the activity in a given occupation, as well as personal, physical, and spiritual suitability for satisfactory performance in it, can apply for and be selected or appointed to any occupation (see 9.3. and Figure 6.0.5.)

An applicant must prove their readiness, and those responsible for decisions must create a system of necessary criteria, make it public, and involve a sufficient number of professionals in the decision-making process. Following the competency principle, no one should get into any occupation by chance. This is the only way to ensure that an unjustified authority structure does not gain traction.

It could be hoped that the triumph of the principle of competency will lead to learning and self-education becoming part of the lifestyle of the entire population.

COOPERATION AND INFORMEDNESS ARE IMPORTANT

Management as a structural unit is not just a set of people, but a group with qualitative significance, whose members improve and strengthen each other. Management creates strategy and tactics and organizes the functioning of the system so that it is fully accountable for the results (and consequences). A continuous effort should be made to integrate and improve management itself. The logic of forming a manager as a subject of management can be seen in the figure (see Figure 11.1.9.).

Improvements in the management’s sphere can only be satisfactory from the top down, but they only make sense if the opposite direction of the process, from the bottom up, is created as quickly as possible. For example, innovation occurs according to a management decision, (flows from top to bottom, 1 in the figure), but management does not execute innovation, the staff does (2), and therefore, it is necessary to inform the staff as quickly as possible of all the details of the planned innovation, its causes, prerequisites, dangers, and the significance of the results. At the same time, everyone should be informed that, in connection with the qualitative improvement of the organization, everyone can expect a wage increase.

To achieve consistency, efforts must be applied both horizontally (3) and vertically (4). In other words, staff must be equally informed at all levels of regulation and on all lines of activity (engineering, technology, equipment, sales, accounting, etc.). There must be sufficient integration of management (5) so that there would be consensus, if not unanimity, and there would be protection against all kinds of attacks and other dangers, as well as communication (mutual informedness) with all those on whom the organization depends and who depend on the organization. After that, you can be quite sure that there are enough efforts for cohesive activity.

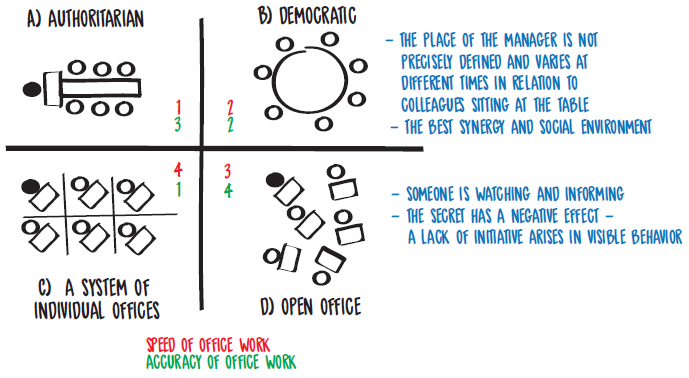

Four options were used to organize the process of solving routine tasks:

1. The manager sits apart: hands out orders, makes comments, gives assessments, and inspires solutions.

2. Participants are seated around a round table, with the manager changing her position from time to time, thus emphasizing that all places are equally important.

3. All participants of the experiment sit in separate rooms. No one is watching, monitoring, or rushing anyone.

4. Everyone sits in the same room, but separately. Everyone knows that someone is watching everyone, taking notes about each of the participants, and later secretly reporting to someone.

Speed and accuracy of problem solving were taken into account for evaluation.

In terms of speed, the groups were as follows: A, B, D, C. In terms of accuracy: C, B, A, D (NB! Group D made so many mistakes that the result cannot be considered satisfactory at all).

Although the round table (B) was only in second place in both speed and accuracy, it was the best overall.

A prerequisite for developing innovation is the balance of management and execution, as well as governance and subordination. It is impossible to make changes in an organization if its management or owners (in the case of state enterprises, this means representatives of the owner) are against it, or do not understand why this procedure is necessary.

Management should ensure that within the organization there is knowledge about all the systems that make up the metasystem (7). Then people will not be afraid of being given something they do not want, or not being given something they would want. Value and reputation are formed in several contexts (8).

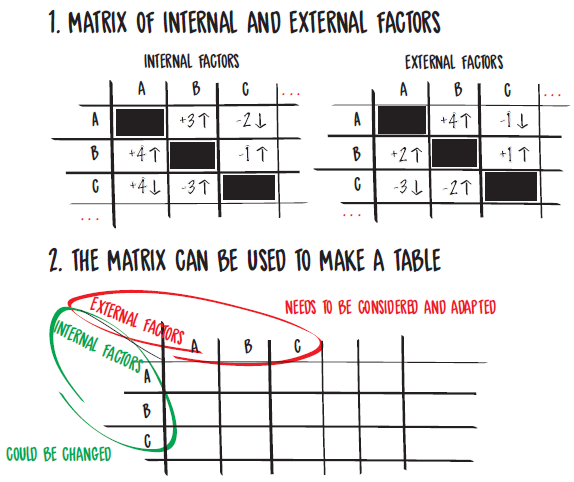

MATRIX ANALYSIS

If we want to change something, it is necessary to identify what the area of interest depends on and what should be dealt with in the event of change. Usually there are so many factors that it is not easy to identify and prioritize what is important. To overcome this obstacle, it is worth conducting a matrix analysis.

Matrix Analysis Steps (see Figure 11.1.11.):

Step 1. Write down, if possible, everything on which the area, phenomenon, or process depends. You can think up success factors yourself or determine them using appropriate reference books, involving experts, or by brainstorming (see 11.4.).

It is necessary to ensure that the list of factors does not omit anything fundamentally important, and at the same time, that there is nothing unnecessary. When making a matrix, do not forget about the little things. Otherwise, it may happen that seemingly insignificant details will be the main cause.

It would be expedient to divide the factors into two types — internal and external. Internal factors are those that we ourselves can change. External factors are not subject to our will and must be treated as inevitable.

Step 2. Make a matrix where the columns and rows will contain the same internal factors, e.g., A, B, C. The first entries will assess how factors affect each other (how A affects B and C, etc.; then, how B affects A and C, etc.). Enter “+”, “-” or “0” in the matrix cells, which will indicate a contributing, hindering, or neutral (zero) influence.

With the second entries, you can assess the strength of influence, for example, on a scale of 1 to 10. In addition, you can assess whether the influence is increasing, decreasing, or stable by adding an arrow pointing up, down, or horizontally to each cell in the matrix.

You can then proceed to add up the scores horizontally and vertically and figure out which factor has the greatest influence on the others (as a whole), and determine the influence rating.

You can make a table of factors, from those that had the strongest positive influence to those that had the strongest negative influence. Then you can make the same table relative to the most influential factors.

Step 3. A similar matrix should be made for external factors.

Step 4. A table of ordered chains of internal and external factors allows you to draw conclusions for creating a strategy and tactics. You can consider the possibility of creating sequences or networks (sets of factors) to generate changes that cannot be directly achieved.

- Development is a chain of qualitative transitions on the way to improving the self-regulatory system.

- Development is objective. We cannot develop something or someone.

- We can create and maintain the prerequisites for development.

Matrix analysis is quite timeconsuming and requires quite a lot of effort (it would be commendable if some computer genius would make people happy with a suitable application for this). After a matrix analysis, clarity comes, different people have an even understanding of the prerequisites for success and the obstacles to it, and their views on priorities are aligned.

In this book, we consider only issues common to all areas of life, but each institution and each organization is unique, with different characteristics, strengths, weaknesses, expectations, dangers, needs, and goals. What is outlined here can, at best, serve as a guide in determining the directions of searches, but no more. However, you need to be independent in the search itself!

NOT ALL TRAINING COURSES ARE USEFUL

It is believed that all learning is useful and necessary. Unfortunately, there are at least three reasons why training courses can do harm:

- The courses do not encompass the whole, looking only at fragments. However, each fragment gets its meaning depending on the context. Context is destroyed as a result of taking such courses, and at the end of them, a person is even more confused than before.

- Attending courses in different places leads to confusion. Since terminology and conceptual understandings differ from course to course and from country to country, this can make further cooperation difficult.

- If course participants come from different places, it is impossible to take into account the characteristics of cultures, institutions, organizations, etc. If courses are not related to the written and unwritten rules of a given society, culture, and organization, then only general principles can be considered, but such abstract knowledge is difficult to apply in practice.

It is advisable to conduct training aimed at improving management within an organization, where participants have a clear understanding of the context and the causes of deviations. If we are talking about engineering, energy, technology, etc., then there will be no difficulties, but if we are talking about organization and management, then it is necessary to take into account people’s relationships, subordination, traditions, and characteristics. In this case, intra-organizational courses with elements of research, design, consultation, information services, and interaction will be effective.

11.2. DECISION-MAKING

Decision-making is the core of the idea of what it means to be a citizen, the use of civic rights, and the execution of civic duty. Decision-making is a key issue in every sphere of social life and at every level of regulation. Decisions can be made individually or collectively and collegially. Each option has its pros and cons.

GOAL-ORIENTED ACTIVITIES AND PROCESSES

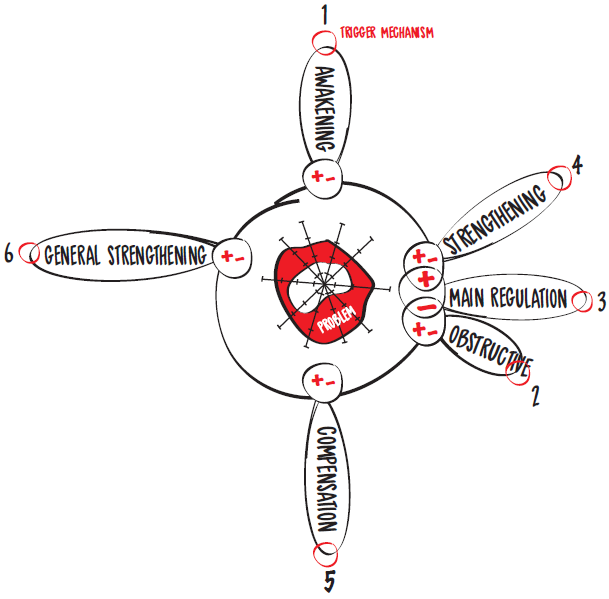

All stages of decision-making should be disclosed both statically and dynamically. Both can be seen as a problem. To do this, it is necessary to find all possible characteristics important for making decisions and, based on analysis, establish their current and desired level. Then, by comparing these levels, it is possible to identify problems and, in a good case, also the causes of problems and ways to reduce (or eliminate) possible complications (see also Figure 11.2.5.).

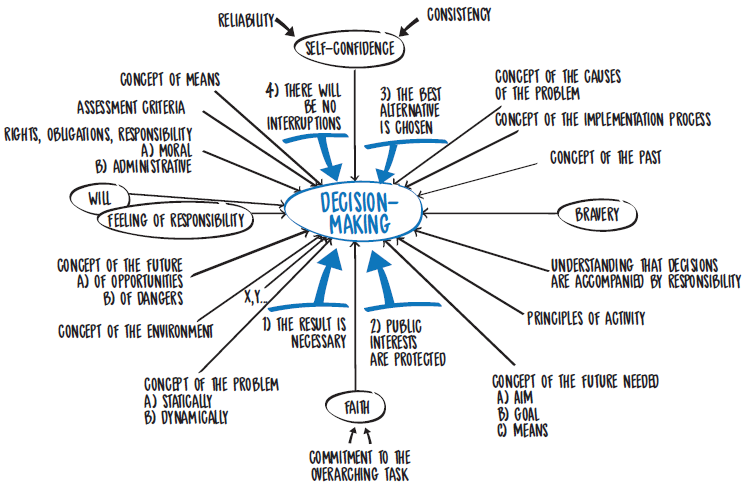

Then, with the help of the figures, consider what making the decision and its acceptance and execution depend on and how it proceeds. The unknowns x and y are present in all figures, which means that these enumerations are not and cannot be complete. Time and circumstances change, one thing or another is added, and some factors may lose their former significance.

The models presented in this book are provided only as an introduction and a starting point for independent search.

The first figure (see Figure 11.2.1.) shows some decision-making factors. Each person can determine for themself what of the above has already been thought out and taken into account, and what needs to be checked and thought over.

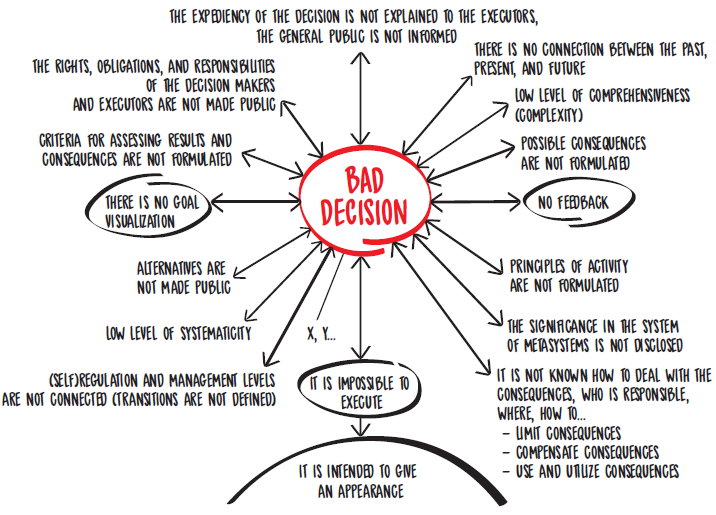

Big decisions are based on the results of system analysis. But before the decisions themselves become the basis for activity, they need to be heard and accepted by those who have the right and the obligation to make sure that the decision is the best possible one. The next figure (see Figure 11.2.2.) shows a number of criteria that can be used to check whether a decision is correct or not. There is also our version of a bad decision, just in case (see Figure 11.2.3.).

Decision-making is and will always remain creative, there is no determination (predestination), and it is not worth it to search for the current norms constantly and in all cases.

If the decisions are good, they should be executed (see Figure 11.2.4.). Most of the prerequisites necessary for executing a decision are shown in the figure, and we will not go into them in detail.

DECISION-MAKING IS ALWAYS ACCOMPANIED BY RESPONSIBILITY

As the reader will remember from previous chapters, the person to whom this or that decision belongs must also be responsible for what happens in the future: who will do what, how, where, and when; what will be achieved or lost. People who have the right and opportunity to decide and for whatever reason have not exercised that right and opportunity must also be held accountable for their choices.

Setting a goal, choosing means, assessing, making conclusions, etc. are nothing but a series of decisions.

We must remember that it is possible to decide only in a situation of choice (see 3.2.). In a situation of coercion, there is no freedom of choice, and a person must either do what is ordered or do nothing at all.

A decision is a search (in given circumstances, condition, and situation) for the most appropriate opportunity and an act of willful expression of that, which is turned into execution.

Any decision is accompanied by the obligation to be responsible not only for further activity, its participants, and the immediate results and consequences, but also for the living environment, both in the near and distant future.

To make a quality decision, you need to be able to encompass the whole, of which the decision is an element. Otherwise, it is difficult to sufficiently imagine what would be necessary to achieve and how to execute the decision, as well as what else might accompany the decision (see Figure 11.2.5.). It is necessary to go deeper into the details presented in the figure and notice for yourself that it is useless to be only educated or informed; you need the unity of education, informedness, and experience. There must also be the unity of rights, obligations, and responsibilities, not the first, second, or the third separately. At the same time, it should be kept in mind that all three components function in both an administrative (formal) and moral (informal) sense.

The golden rules of decisions:

- Do not decide what others could and should decide for themselves.

- Help colleagues and others reach a level where they could and would be capable of quality decisions.

- The time spent on consulting col-leagues can be considered more successfully used than the time spent on personally performing the same task.

It is important to note that every decision has three stages: the decision must be made (formulated), accepted (realize its necessity), and then executed. Two crucial phenomena emerge from decisions that are often more important than the decision itself. These phenomena are the sense of responsibility and activeness of those involved in making the decision. If a person has made the best choice between alternatives, they are interested that the choice will be executed — this is activeness. If a person has made good decision, they have thought how to minimize possible consequences and how to achieve maximum results — this is sense of responsibility.

It is important to consider that a good decision is one whose realization is partly through goal-oriented regulation (management, governance, etc.) and partly through self-regulation. Self-regulation should be primary. As the reader already knows, with the help of management, it is possible to achieve the necessary conditions for self-regulation and to reduce the need for managers and management (the ideal of self-regulation would to achieve direct management to become redundant).

Under the given conditions, circumstances, and situation, making a decision is the choice of the most appropriate opportunity, an act of will presenting a person’s preference and transferring it into execution.

In addition to the results of goaloriented processes, there are always (!) consequences — no one wants them, but they occur anyway. For example, defects and waste in production, depreciation, accidents, etc.

A good decision is one whose realization is partly through goal-oriented regulation and partly through self-regulation.

Therefore, it is necessary to do everything possible to ensure there are as few consequences as possible. At the same time, it should be thought through in advance how to respond to them and what to attempt.

ASSESSMENTS, COMPROMISE

A decision is assessed on the basis of its execution and the results and consequences accompanying its execution.

Every decision can be to someone’s liking and at the same time be unacceptable to someone else. To reach a compromise (see also 12.2.), all the pros and cons must be weighed. Arguments can be direct and indirect, public and hidden (latent), manifest here and now or later and elsewhere, locally or globally.

The source of power in society is alternatives.

To reach a compromise, the sides should give up some part of the original plan (something they considered desirable or necessary). Often people are faced with a moral dilemma: whether, in the name of compromise, to give up their ideals and lofty ideas, myths and taboos, while achieving a result that gives the opportunity to take a break and restore resources, to analyze themselves, to restructure, or whether moral compromise seems fundamentally unworthy, unacceptable. Unfortunately, it is not often discussed in our society whether dignity can be maintained by making an undignified compromise.

- The only way for us to gener-ate a sense of responsibility and activeness in society is to help people form as a subject of selfgovernance and social management capable of independent decision-making.

- In other words, it means creating the conditions for each person to become a citizen and behave as befits a citizen.

Compromises, for the most part, are temporary solutions because they satisfy no one. Compromises are usually resorted to due to powerlessness in a situation of coercion.

Before embarking on big decisions, it is advisable to outline at least three scenarios (“rosy”, “green”, and “black”, see 2.10.) and create alternative strategies for executing possible decisions. It would also be advisable to think of something to make up for the compromises, to compensate for the values sacrificed, to restore the losers’ self-esteem, etc. In China, they say that those who want to win should build a golden bridge for the loser to retreat. It is important to understand that otherwise the confrontation is only prolonged.

STRUCTURE AND PARTS OF A DECISION

A decision is always an expression of will, or vice versa, a sign of reconciliation with inevitability. A decision might be formed as a document with a complex structure.

A decision characterizes, first of all, the maker of the decision, their interests and perceptions, education and informedness, expectations, fears, etc., as well as the era, conditions, circumstances, situation, and organization (see also 7.).

When assessing a decision, it can only be partially assessed. The greatest weight is the totality of the results and consequences accompanying the execution of the decision.

The preamble to a decision explains (and in practice, as we see, these are often hidden): who is the decision-maker, why and for whom the decision is needed; what is going to be regulated by the decision; what parts the decision consists of; who drafted the decision; who made what amendments or cuts; to whom the makers of the decision are grateful. In some cases, some of the parts mentioned here are presented in a cover letter.

A cover letter may describe the conditions, circumstances, and/or situation and the reasons for their formation and existence, as well as trends toward change.

The following should be established in a decision: the subject of the decision; the necessary (guaranteed) means to achieve the goals; the stages of implementation and the timing of their beginning and completion; subordination (who should coordinate their activity with whom and how, and who should report what to whom and in what form); the rights, obligations, and responsibilities of participants; principles of activity; resource expenditure (budget) and conditions for using resources; procedure and funding sources; criteria for recognition or penalties.

The quality of the decision depends on the aim of those involved and the goal set. It can happen that a goal is primitive and formal. Goals about which nothing good can be said, as a rule, are evasion, wasting, economizing, and other similar activities (see Figure 2.10.1.). It is much better when a result or state of being is designated as the goal. Results are achieved through actions, states of being are achieved through processes (many actions). Therefore, it is not reasonable to prescribe actions or processes as a goal.

SUBJECT AND OBJECT OF DECISION EXECUTION

The subject of a decision’s execution should have a clear understanding of the following:

- the initial and desired conditions;

- the ways to achieve the goal and the hidden dangers and opportunities of each way;

- the process as a whole and its stages;

- the problems and their causes at each stage;

- alternatives and scenarios;

- the principles of activity and the basics of assessment;

- creativity and ensuring the freedom and order necessary for creativity;

- work and cooperation;

- assessment as a procedure (who, where, when, and how to assess);

- the procedure for presenting results;

- connection, as well as goal visualization and feedback;

- the ratio of aim-keeping activity to goal-oriented activity, and the ratio of situational, coercive, and chaotic activity;

- responsibility both personally and culturally, as well as in the occupational sense.

The object of a decision may be a system or some of its parts, their properties and factors, including cooperation, subsystems, and metasystems; factors of functioning, changing, and/or developing the system; factors of stability, expediency, efficiency, and intensity; and the material, immaterial, and/or virtual environment of the system.

The focus of those responsible for decisions may be:

- a certain number of people, their hopes, interests, needs, relationships, communication, life and its structure, well-being;

- single actions, the content and form of activity, rhythm and tension, significance and meaning, necessary and prevailing conditions, results, payment and other compensation;

- an activity system;

- a culture of activity;

- a process or system of processes;

- prerequisites for success;

- a strategy and tactics;

- assessment criteria and the system for applying them;

- principles and a system of principles — for drawing conclusions;

- a system of goals, needs, and tasks — for presenting proposals;

- a system of resources and the conditions necessary for their use — for presenting advice;

- a connection for achieving mutual awareness;

- the prerequisites of goal visualization and feedback — for achieving expediency and efficiency;

- mechanisms of regulation and their importance in ensuring the logic of activity;

- mechanisms of influence and their influence on forming results and consequences;

- triggers and their effects — for achieving the required intensity and efficiency;

- factors that contribute to and hinder the system functioning, changing, and developing.

A decision can be made to:

- ensure the functioning of the system, support change;

- increase the likelihood that the changes will lead to the goal, will take hold, and will become irreversible;

- form prerequisites for qualitative transitions, that is, for development.

Change makes it possible to stay on aim and achieve goals.

ON THE ROLE OF THE ADVISOR

In some cases, each person is able to cope independently, and in some cases, it is necessary to act together; sometimes it is worth doing research, and sometimes it is enough to have advisers. Profane people need advisors to conceal their own level.

Advisors may be needed for:

- achieving a sense of confidence;

- understanding about being informed and to value information;

- discussing alternatives;

- ensuring that interpretations are systematic and comprehensive;

- revealing the specifics of the levels of regulation;

- foresight and accurate recognition;

- orienting in the specifics of relationships and interaction;

- taking into account opportunities and limitations;

- rationally using time and space;

- ending the urgency caused by superficiality, notions of the honor of the uniform, fear, etc.

An advisor can be useful if they were brought up in the context of the same social and cultural connections and are a professional, a person with clean hands and a big heart (not petty, not greedy, not vain, etc.), and also if they:

- are impeccably honest, ready to help, caring and attentive;

- do not meddle with advice, but help to foresee and recognize both opportunities and dangers;

- help to avoid mistakes and find the optimal solutions;

- know a lot. NB! They also know what they do not know and are brave enough to inform others about it. They do not present themself as a professional in areas in which they are not;

- unmistakably distinguish knowledge from opinions and beliefs (do not confuse them with each other and do not let others get confused);

- know the connections of the past, present, and future, and know how to take them into account;

- have a sense of proportion and understand where the boundaries are.

- An advisor sells (if they sell) only their time and nothing else!

- An advisor does not succeed; it is the person who invited the adviser to be an advisor who succeeds.

An advisor can be useful if they are delicate; if they do not point out to others their faults and misconceptions; if they do not make secrets public and do not tell anyone about whom they are advising and on what matters. An advisor sells (if they sell) only their time and nothing else! An advisor does not succeed; it is the person who invited the adviser to be an advisor who succeeds.

An advisor makes every effort to ensure that, in the future, clients will be able to cope on their own, independently. Practice shows that if an advisor takes into account all of these requirements without exception, their services will be in high demand.

BIG AND SMALL, GOOD AND BAD DECISIONS

Decisions must be timely, prepared quickly but not in a hurry, sufficiently systematic and comprehensive, with the required depth and breadth, in accordance with expectations in the cultural and social context, and with the participation of those directly affected by these decisions. When making a decision, it is necessary to make sure that implementing the plans will not harm human health, nature, and culture.

Any attempt to conceal the decision-maker (the responsible person) sooner or later leads to bureaucratization and other dangerous consequences for society.

No decision should constrict the prerequisites for population growth, affect the interests of families, mothers, the environment in which children and young people grow up, the execution of parental duty, and the ability of children to care for their parents. The population and its growth are of existential importance for Estonia. As an endeavor, population experts could be asked to approve and endorse all parliamentary and governmental legal acts. Similar advice was already given in the late 1930s by Estonian Prime Minister Kaarel Eenpalu: when drafting every bill, the main emphasis should be on ensuring that the laws do not hinder, but facilitate population growth.

It is necessary to distinguish between making a decision and a decision itself, its acceptance, and execution. Each of the stages above has its own prerequisites, results, and consequences.

Good decisions are prepared by teams, but are definitively made by individuals who must take responsibility for both the activities that follow and the results and consequences that accompany them. Any attempt to conceal the decision-maker (the responsible person) sooner or later leads to bureaucratization (see 12.3.) and other dangerous consequences for society.

- Transitions from one stage of execution to the next pose a particular danger to decisions;

- For example, a decision is made unanimously, but no one is in a hurry to execute it. What is started is abandoned halfway through, because the decision does not meet the requirements of the next stages.

In organizations, decisions are executed by teams, but the top manager is responsible for the results and especially the consequences. Consequently, the organization must have some form of interim reporting.

The prerequisites of decision making are, on the one hand, the unity of education, informedness and experience and, on the other hand, the unity of rights, obligations, and responsibilities. NB! All six, both formally and morally.

Execution of a decision is either a goal-oriented (guided) process, or self-regulated. When decisions are executed, in addition to the results achieved, there will be negative consequences and could be unexpected positive side-effects.

Decision making is possible only in a situation of choice (see Figure 3.2.1).

A substantial part of each civil servant’s and MP’s salary is apportioned for taking risks (courage to decide, to think critically, to create, to stimulate the creative process).

As a conclusion and for greater coherence of the reasoning here, as well as reflections on transitions, we present another figure (see Figure 11.2.5.). We have looked at the stages of decision-making and execution, but the nail in the coffin of all decisions can be transitions. For example, a decision is made, but no one rushes to execute it; a decision is executed, but no one is willing to assess the results and consequences; results and consequences are assessed, but no one takes them into account and does not make adjustments; something is learned, but the acquired knowledge is not used, etc.

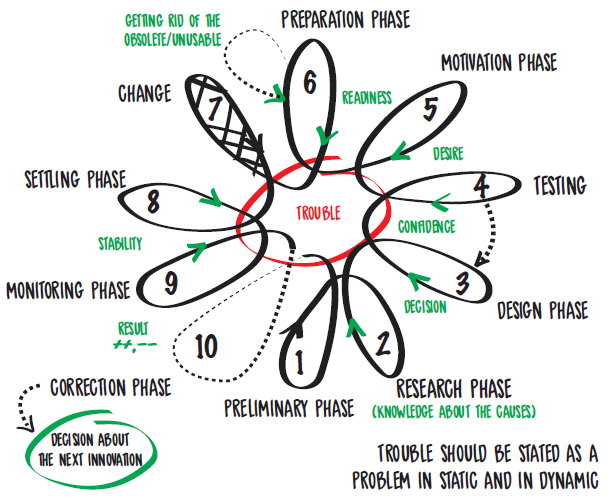

11.3. INNOVATIVE PROCESS

Some changes in everyday affairs occur constantly. Here we will look at fundamentally important changes.

The first thing to remember is that the moral right to change something arises only when what must not be changed is well protected and preserved. Destroying values is not difficult and, compared to creation, the process can proceed very quickly — without the principle of personal responsibility, destructive activity becomes usual practice.

- Innovation is an aim- and goal-driven update directed at changing the functioning of a system.

- The transition of a system to a qualitatively new state of being is development.

- Many innovations can be planned to facilitate development.

Innovation as a process is a chain of events in a temporal sequence and logical connection, through which the system achieves the adoption and consolidation of fundamentally important changes so that after the innovation, the system functions more smoothly and confidently than before.

Innovation is carried out by the people themselves or the workers of an enterprise if the managers create the prerequisites for it. Innovation is not a self-regulating process — it is a regulated process.

The first thing management should do is formulate the problem (see Figure 0.3.3.). This is necessary if the following is determined:

- If there are no updates, there is a threat of lagging behind.

- There is evidence of changing market conditions and consumer structure in the world.

- The current conditions are not satisfactory, the trends of changes are troubling, there are only some assumptions as to the causes.

- There are a number of ideas, but it is not known which one is best for changes.

- It is known who is able to plan and prepare the innovative process.

- It is known that in case of innovation, there is hope to keep the consequences under control. Irreversible dangerous processes will not be caused, the foundations of self-regulation will not be destroyed, and the viability of the system will not be jeopardized.

IT’S IMPORTANT NOT TO MISS THE MOMENT

Usually, innovation is accompanied by a decline, because it is impossible to continue activity in the old way, and the new way is not yet possible. In order to ensure that this decline is not too steep and prolonged, it is necessary to gather resources in the previous phase to overcome it and move to the phase of the expected rise.

Practice shows that if you are late with implementing innovations, the decline can be quite steep.

Finding the right time to start an innovation is not easy. It is necessary to make a strategic decision that takes into account a large number of contradictory factors. It is advisable to begin innovation when the organization is still on the rise, but there are already the first signs of an emerging crisis (see Figure 11.3.1.).

The reason for a significant part of innovation could be the environment. The second serious reason could be a change in market conditions and consumer structure. The third reason could be scientific discoveries and related changes in engineering and technology. Of course, the reason for innovation can be depreciation of equipment, buildings, etc., relocation, a radical change in the direction of activity, etc.

It is advisable to begin innovation when an organization is still on the rise but there are already the first signs of an emerging crisis.

Innovation is a necessary and quite natural component of social development. The year 2009 was declared the Year of Innovation in the European Union. Numerous seminars and conferences have been held on this subject in all EU member states. Despite this, innovation processes are still varied. If the organizers of the Estonian administrative reform in 2017 had at least some training in innovation, there would not have been all the confusion and mess that we saw in the end.

EVERY INNOVATION IS UNIQUE

There are small, medium, and large innovations. There can be no standards here — every innovation is unique. Below we can consider only some of the fundamental issues.

It is natural for a citizen to want to make sure that innovation is appropriate, that there are all the prerequisites for dealing with its implementation, that nothing bad will happen because of innovation, either here or elsewhere. If there is a suspicion that management is beginning to embellish or falsify, any competent representative of the highest authority (that is, every citizen!) not only has the right, but the obligation to intervene and demand clarity. It may happen that management will not want to pay attention to such demands and thereby loses credibility, and executors, for their part, lose the taste for cooperation. It might also be vice versa and cooperation to carry on innovative process would follow.

To succeed, innovation requires:

- a leader who is believed and trusted by colleagues;

- a cooperative team in which everyone already is or wants to be:

- professional,

- well-intentionally demanding and ready to give support,

- wholeheartedly devoted to the cause,

- honest, fair, and trustworthy in every sense.

There is a high probability that innovation will be a failure if participants are not informed about the reasons and goals of the innovation, and motivation is clearly insufficient if people feel that updates are made at their expense and not in cooperation with them, if work is added, risks are increased, and wages are reduced.

A person is fundamentally capable of changing the human-made or material environment. This cannot be said of the immaterial environment. A person can only identify the factors that shape reality and hope that under the influence of changing the system of factors, something will begin to form that can be useful, that would be an order of magnitude better than the existing one and open to further improvement at the same time.

Innovation as a science studies the logic, types, and principles of updating, updating as a phenomenon and as a process, and the circumstances contributing to updating and complicating the updating process. There is no hope of acquiring an understanding of innovation in a “read–learn–do” way. Innovation is creativity! Here, too, we can look briefly at just a few details in order to emphasize their importance and to advise every innovator to think carefully about them in the context of their searches.

You can plan and manage innovation as a process, but you also need the result of innovation, through which the system can function more smoothly and become more reliable and accurate. The result of organizational innovation may be a more appropriate structure than before, a clearer division of labor and responsibility, a team where mutual demand and willingness to cooperate prevail.

Again and again, we should remind each other that in order to implement any innovation of any significance that affects human life and health, nature and culture, it is necessary to have a moral right along with a formal right. Management by itself does not make innovations — they happen with management’s support and assistance.

The better the innovation proceeds, the clearer the update is interpreted as an opportunity rather than an obligation. If a person understands that it is unwise to continue the old way, that the update is well thought out and the result is highly sought and enjoyable, then they may be happy with the update. Of course, management should create conditions for the innovation’s direct participants in which they would like to make efforts and do everything possible to overcome the hassles associated with the updates. It may happen that innovation will increase the workload and expand the scope of responsibility. Separately, we note that any innovation must necessarily be accompanied by an increase in wages.

INNOVATION TO ACHIEVE QUALITY TRANSITION

As an example of the innovation of a large organization, here is a model [1] (see Figure 11.3.2.), that has been an integral part of curricula at several universities. Perhaps this interpretation will encourage citizens to think outside of academic institutions, as well.

Being inside any system, at best a person can only discern parts, subsystems, and elements of the system. In order to see the system as a whole, it is necessary to look at it from the outside, and to find quite a few points of view for this. Figuratively speaking, it is impossible to describe a house when you are inside it; to do that, you have to go outside and look at it from several angles.

There are at least ten stages that must be gone through.

- A preliminary stage, in which the concerning deficiency is framed as a problem both statically and dynamically. Practice shows that appropriate models should be created for this.

- Research to identify the causes of the contradictions that led to the decision to innovate. More precisely, the system of causal (reasons) and functional (co-dependent) connections should be identified, formulated, and published. When they are found, focus on the “3+5” rule (see 13.4.).

- Designing, during which a decision is made.

A satisfactory decision contains at least:- Representation of the current conditions, circumstances, and situation (A) both statically and dynamically.

- An idea of the desired conditions at this moment (circumstances and situation) (B).

- Justification why it is impossible (prohibited) to further tolerate the contradiction between A and B.

- A list of the causes of the problem that could be identified and formulated during the research stage, by degree of importance (priorities).

- Aim and goal (expedient direction and state to be achieved by a certain time).

- Alternative ways with all their pros and cons.

- The preferred decision in conjunction with the arguments that prompted this choice as the basis for further action.

- Stages of achieving the goal and ensuring consistent goal visualization.

- Principles of activity.

- Criteria for assessing the activity, participants, and results.

- Measures to ensure continuous feedback.

- An activity plan that describes who does what, as well as in what time frame and to whom the result is to be delivered.

- Preferences for how to act in the name of achieving the new conditions (B) and reduce the likelihood of dire consequences.

- Direct and indirect responsibility and the right of program participants to act independently and fulfill their obligations.

- Reporting.

- Testing, during which you can try out both the idea itself and the procedure for implementing it. It may happen that the idea fits all the parameters, but the procedure is poorly planned. Or vice versa. In both cases, go back to the beginning and make a new decision.

- Motivation — an actively friendly and supportive attitude should be achieved on the part of those people directly or indirectly affected by this update.

- People with clear motivation participate, support, improve, protect, etc.

The presence of motivation is more important than it may initially seem. If the executors are not ready to contribute and do not support the changes themselves, it can happen that even an innovation based on a great idea will drag on for a long period or fail.

- Motive galvanizes a person into action.

- Motivation (a set of motives) is focused on the future and is prospective.

- It is possible to motivate (explain, justify, condone) what has already been done and is retrospective.

- Preparation involves the opportunity to refresh people’s knowledge and skills, to clarify the principles of activity and the prerequisites for cooperation, so that a readiness for updated activity arises. If necessary, changes are made to the structure, new equipment and models (theories) are acquired, all in order to achieve universal competency (consistency) and awareness, as well as to create all necessary conditions for goal visualization and feedback. A separate consideration should be given to the conditions in which innovation is possible only if it is possible to get rid of what is obsolete (and is no longer useful), but persists due to the clientelism that has not yet been broken. Getting rid of the obsolete can be so complex that it requires a separate program or a parallel organization.

- Change as such begins when all the necessary preparatory work has been done. The change can take an hour or a day, or it can last for years or decades.

- Sedimentation. According to popular wisdom, chickens are counted in the autumn. There is also no need to fuss when assessing an innovation. The sedimentation of relationships and the formation of selfregulation in the new conditions will take some time.