CONTENTS

- 0. Introduction

- Chapter 1: PERSON

- Chapter 2: LIFE

- Chapter 3: ENVIRONMENT

- Chapter 4: SOCIETY

- Chapter 5: CULTURE

- Chapter 6: COMMUNICATION

- Chapter 7: ACTIVITY SYSTEM

- Chapter 8: THE COGNITION SYSTEM

- Chapter 9: EDUCATION

- Chapter 10: WORK

- Chapter 11: MANAGEMENT

- Chapter 12: COOPERATION

- Chapter 13: CONCERNS

- Conclusion

Chapter 1: PERSON

A person is not only a resource.

A person and their well-being are the alpha and omega, the beginning and the end, the main goal and the purpose of every decision, and the main principle and the main criterion of assessment.

1.0. GENERAL CONCEPTS

In order to see yourself and others, you need to find quite a few points of view. We are all individuals and identities, personalities, subjects and objects of manipulation, and more. A person is not only a resource!

At the heart of the concept is the individual, the resident, who wants to become a citizen, be a citizen, and act as a citizen and patriot, who cherishes their home, homeland, state, and nation. In order to behave as a reasonable citizen, a person needs to know and be able to understand, foresee, and recognize who and what they are. Only when one has a sufficiently clear orientation in society and culture does one have the courage to decide for themselves and to execute their own decisions as well as those of others.

A reasonable citizen, without any outside help, understands that before expressing an opinion, it must be carefully considered, and before making a final decision, makes sure that what is going to be done (and how implementation is planned) is reasonable and necessary. A citizen is characterized by all human virtues. In regulating behavior, along with the motive of achievement, there is also a motive for preventing failure.

A reasonable person cares what others know and think about them. A reasonable person also needs attention and recognition, and they are afraid of public condemnation that may follow a foolishness that has been done, or if they do not do something important that should be done (not only because of the hopes and expectations of others, or because they would be obliged to do so by official office and status). Human behavior is regulated by a system of dispositions, including ideals and lofty ideas. Also of importance are the overarching task, worldview, sense of duty and responsibility, etc. A large part of the regulation of behavior is occupied by fear and shame, which are formed in cultural ties, as well as a sense of guilt, which is formed in social ties.

A person could be considered:

- as an individual and a personality;

- as a subject or object of manipulation;

- as a member of society and representative of culture;

- as a result, creator, and custodian of the family;

- as a set of roles and statuses;

- as an assumption and an obstacle;

- as a goal and a means;

- as a resource and condition, principle and criterion;

- as a measure and cost to all and everything.

MORALITY, SOCIAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE CONTROL

There are many driving forces. One person is active because he has an interest; another is motivated by a sense of duty; the third, by a sense of responsibility; the fourth, by needs. Some are inspired and spurred on by a sense of home, while others are driven forward primarily by civic feelings.

Someone is afraid of journalism; someone is afraid of fire, thieves or the police, prison, God, condemnation by a class or colleagues, a spouse… If a person does not have a clear mind to understand the difference between moral and immoral, if they have lost their sense of shame, then nothing will help them, and they could stop reading this book right now – there is no point in wasting time. If one is not ashamed to act like a pig or not do what they should, then it means their moral compass is broken. Through training and understanding the system, such a person can achieve the ability to do stupid things on a level never seen before, while becoming a danger to their surroundings and society.

A mild example of the boundary between moral and immoral behavior is a farmer spraying pesticides in the fields at a time when this should not be done, thereby causing the death of the surrounding bees. Legally, this act can look like nothing, but if there is no shame in it, no law will help. Laws cannot replace a system of moral values.

The main mechanism for regulating society is morality. According to estimates, 60% of people’s behavior depends on the norms of morality.

Human behavior and social life are regulated primarily by morality. According to estimates, 60% of people’s behavior depends on conscience — knowledge and respect for the norms of morality. Morality cannot be replaced. If morality does not work, then everything in society is for nothing — organizations, institutions, communities, families, and everything else.

The social control that people exercise over each other regulates about a third of human behavior, but only if these people know and respect each other and consider each other. People prefer to think well of themselves, and since self-esteem is formed through the prism of other people’s views, so comes the desire to meet the expectations of others. If people do not know and respect each other, then social control does not work. If social control conflicts with societal or cultural norms, then disorder threatens to become the norm.

All people are different, each of them has their own:

- views and beliefs, picture of the world and worldview;

- innate inclinations, temperament, and character;

- attitudes and positions;

- expectations and assessments;

- aims and goals;

- interests and will;

- values and norms;

- myths and taboos;

- faith, hope, and love;

- dreams, temptations, and virtues;

- doubts — hesitations, addictions, and fears.

Administrative measures — laws and regulations, all kinds of prohibitions, orders, and fines, no matter who issues them, be they police officers, inspectors, or other officials or agencies — regulate only a tenth of human behavior. Administrative control does not guarantee normative behavior. You can be quite sure that even if you put police officers on every corner and behind every bush, but still do not apply a system of moral concepts and social control, the traffic culture will not improve. Most likely, neither the number of speeding drivers nor the number of drunk drivers will decrease.

Each person’s activity happens simultaneously:

- both in formal and in informal systems;

- both among cultural and social ties;

- both among community and family ties.

INDIVIDUAL, PERSONALITY, SUBJECT

It is relatively easy to describe an individual. To do this, you need to take into account all their demographic characteristics, which are recorded in identity documents — sex, age, ID number, etc. The attributes of an individual are also height, weight, number of years spent in school, marital status, status, and position in the social division of labor, etc.

The individual is a living system, an individuality, distinguished in space-time by their degree of activity and enlightenment (the level of intellectual and spiritual development).

Describing a personality is much more difficult. Personality is a social quality of a person (an individual). Personality is as complex an object of exploration as the cosmos or the universe, which are inherently vast.

The subject — the active principle — can be each person or a set of sufficiently united people who are able to feel, think, act together, and also more or less unanimously bear responsibility. In order for the subject to be able to act productively and effectively based on a sense of duty and responsibility, he should navigate the relevant system and its metasystems; formulate problems (see Figure 0.3.3.), find their causes, and model systems of measures; form decisions (see 11.2.), and execute them; find connections; organize the environment; assess executors, actions, and results; make corrections if necessary; and be responsible for what is done and not done.

At the center of the entire system of training and upbringing is the individual, who is obliged to learn all the knowledge and skills in the curriculum. If learning is goal-oriented and upbringing aim-driven, it is very likely that we will end up with a personality. But it should be remembered that while learning, the student is an individual — a boy or a girl of a certain age with an individual development trajectory.

When people start working after graduation and come to a particular position, they are hired as individuals. Thus, if later it comes to promotion or dismissal, it is because they have shown themselves now as personalities. Anything can happen, and not because they have or do not have professional knowledge and skills.

In creative processes, developmental connections, etc., the personality manifests itself as a subject (actor), moving life forward or hindering it.

If we write out the concerns of the modern school and place them in order of importance, it becomes obvious that in many schools children are still viewed not as an active subject, but as an object of manipulation (see Figure 6.01.). Unfortunately, children often find themselves in similar circumstances outside of school, including at home.

A person who has been raised as an object of manipulation, who has had to endlessly follow the orders and instructions of others, to do only what he is told, is not used to thinking; he cannot and will not dare to think independently or with others, and there is no point in talking about exploration, discovery, and creativity.

Experience shows that if a person from an early age is not accustomed to deciding and taking responsibility himself, then later, like it or not, he will try to avoid decisions and the accompanying responsibility. The consequence of this upbringing is a workforce that, after a long time in school, knows quite a lot, but has little skills to use the knowledge and almost no understanding what it is proper or improper in society. Part of this workforce is referred to as specialists.

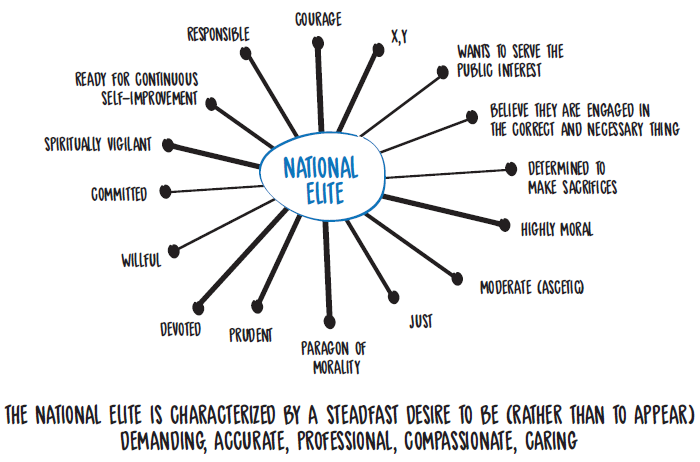

Society is not led by doers, but by creators capable of perceiving reality as a whole, who are able and willing to behave as subjects and serve as a national elite in the public interest (in this book we call such people generalists) (see 1.7.).

If a person from a young age is not accustomed to deciding and taking responsibility himself, then later, willy-nilly, he will try to avoid independent decisions and the accompanying responsibility.

ABILITY AS THE GREATEST ASSET OF EVERY NATION

A person’s greatest asset is their ability, their innate gifts. The greatest asset of a nation is its citizens’ abilities, not coal or oil. Discovering an ability early, treating it with care, and creating a system to ensure that it could form into talent matters of shaping the future of every nation. Parents and all those who come in contact with the child should safeguard ability as the apple of their eye, treating it with tenderness. Nature or the Creator is often generous in some ways and stingy in others.

For example, a person may have an excellent memory, imagination, the ability to generalize, etc., but suffer from such weakness that they are unable to see things through, unable to solve the simplest questions and to act systematically; such a person has difficulty even getting out of bed in the morning. To help them, it is necessary to act in two ways: protect the natural abilities and strengthen the weaknesses. With targeted activity, weaknesses could be ironed out, at least to the point where they do not have destructive power.

An important role is played by growth environment, which provides support, compensates for weaknesses, and protects and defends natural gifts.

A single factor is not enough to achieve success. At the same time, any weak factor can cause failure. People are capable of many things, but not all and not everything.

It should be noted and remembered that all children are talented. Understanding this is one of the key civic positions. Everyone can be more capable of something than another, and it is advisable to build your life path in the direction in which the Creator (nature) has been particularly generous towards you.

The development of the subject at every stage of life depends, first and foremost, not on learning, but on creativity. The more time, space, and rights given to creativity, the greater the hope for development and continued success in any field of activity.

In order to see yourself and others, it is necessary to:

- know what to look at and how to look at it;

- be able to find numerous points of view;

- be able to comprehend what you see from different points of view;

- be sufficiently demanding that you don’t miss anything significant;

- consider that a person has desire and interest, and that a person may change;

- know that communication is possible if the parties are sufficiently similar, and that communication is meaningful if the parties are sufficiently different from each other;

- understand that everyone has the right to be special, unique, and admirable.

LIFE PREREQUISITES AND ARC OF LIFE

It is important that a person is able to consider every moment, day, week, year, and entire life as one whole, so that they notice events, stages of life, and prerequisites. That is why it makes sense to compose your personal arc of life (describe your life path) and analyze it. In everyone’s life there is birth, rising, maturity, and if you are lucky, old age, etc. In the process of drawing the arc of life, one can reflect on the stages that have already been passed and those that are yet to be passed in the near or distant future.

NB! Each period of life has its opportunities and dangers, its pluses and minuses.

It is important to plan everything in advance and prepare yourself for all stages of life’s journey. It’s too late to start preparing for the stages that have already begun. Education as a lifelong process is also a means of building this kind of preparedness.

At every moment, you should prepare not only for the next stage, but also for the stages that follow. At each of them all objective laws play a role — both the laws of nature and the laws of society and laws of logic. They manifest themselves as patterns. To live satisfactorily, they must be understood and reckoned with (see 2.8.).

If characteristic patterns are ignored at any stage of the arc of life, the consequences will not manifest themselves at the next stage, but at a more distant stage, at a moment completely unknown to us.

Many people have probably noticed that preschoolers at a certain period have an irresistible desire to draw. Then they should be given paper, like bread, so they can graphically express their emotions. If at this stage of the child’s life, which is dominated by the emotional desire of self-expression, we instead occupy him with rational and guided activities — reading, writing, and arithmetic — then, of course, we will get a well-prepared and brilliant student in the first grades. However, already in the fourth or fifth grade, a delay in emotional development that occurred at the preschool stage may manifest itself: suddenly there will be behavioral concerns (aggression, apathy), social disorders (difficulties in communicating with peers and adults), and an aversion to learning. These disorders begin to intensify if punishment follows for the behavior that caused them. The consequences of a parenting mistake once made can accompany a person throughout their life.

ABILITY TO SEE AND HEAR, PATTERNS OF THINKING

Above, it was about how to see yourself and other people. Now let’s see how to perceive the things, phenomena, and processes taking place around us. Looking and listening makes all the more sense the more our eyes and ears are tuned to notice both the whole and the concrete, both subsystems and elements, both a state of rest and motion. Understanding is possible if you have thought models (theories) in your head (see 7.3.) for interpreting what you see and hear according to the cultural context. It should be recognized that the ability to see depends not so much on vision as on mental abilities, the ability to think, including thinking concretely and abstractly (generalizing). Visual perception is elementary compared to the ability to see systems and their meaning.

It is possible to see the whole, its parts, subsystems, and elements; it is possible to foresee dangers, opportunities, obstacles, and alternatives. You can recognize and describe right and wrong, fraudulent schemes, the ability to reach compromises; those who are fair and deserving of respect, as well as cheaters, players greedy for personal gain, etc.

The ability to see depends not so much on vision as on mental abilities, the ability to reflect and identify what is behind various processes and phenomena.

In order to see the whole, as well as connections and dependencies, you need to follow appropriate models of thinking (theories) and systems of principles (methodology) (see 7.3. and 8.3). You also need methods (the Greek method is a path; a tried, reliable road that helps you keep on track, achieve goals, fulfill obligations and tasks) and experience, the ability to listen and be silent, not to glance in passing, but to look long and several times, under various conditions, etc. Using the observation method, it is possible to collect reliable data if the observer has previously thought through and decided what exactly they are observing and how to record the observation data. Similarly, it only makes sense to open the hood of the car if you know what the engine looks like in working order, and what can happen to the engine in principle.

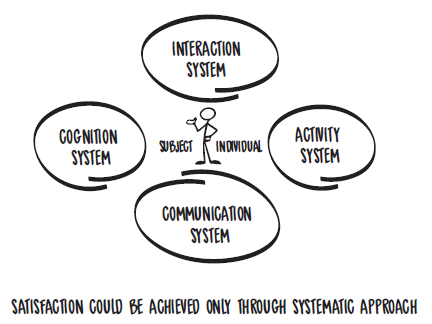

ACTIVITY SYSTEM AND COGNITION SYSTEM

The human activity system (see 7) has a complex structure. In each period of time, an adult lives in a role and behaves as the circumstances, conditions and situation allow or dictate. The concept of a situation also has its own structure and characteristics (see 3.2.) In a situation of cooperation, there is a search for compromises and opportunities for mutual assistance; in a conflict situation, people confront each other. Instead of searching for a suitable solution, the warring parties try to win by destroying the opponent or, if not completely and permanently, by pushing them away for a long time. A person in a problematic situation is sure that there are several possibilities for overcoming the contradiction that has become an obstacle — it was just not possible to find the best solution from the beginning.

In a problematic situation, a person is open to various kinds of searches: they read, research, debate, consult. If a person thinks that there is no satisfactory way out, because all possible ways are unacceptable, then they are in an absurd situation. A person in an absurd situation may fall into apathy (see 3.3.) or become aggressive both toward others and toward themself.

- Circumstances are general and institutional opportunities, with no clear time constraints.

- A condition is a state fixed at a specific time in a multidimensional space.

- A situation is how a person finds themself in given circumstances and condition.

People who find themselves in a real (true) situation behave differently from those who think they are in a game situation. The latter, instead of being, are trying to show.

NB! A game (see also 7.1.) is a serious activity that requires special effort, during which it is customary to behave as accurately as possible following the established rules as long as the game continues. In the case of a game situation, however, a person fools around, tries to leave a mistaken impression, leads someone by the nose, etc.

It has long been known that in a situation of a shortage of time, a person makes many mistakes, they are superficial and quickly get tired. We now know that in a situation of excessive time, human behavior leaves even more to be desired. However, it manifests itself in a slightly different way than in a time-shortage situation.

It is possible to make a decision only in a situation of choice.

In a forced situation, there is no freedom of choice and nothing can be decided. A person can decide (see also 11.2.) only when they feel they are in a situation of choice (see 3.2.). In a real, true situation of choice, a person understands that deciding, refusing to decide, and postponing a decision until the future is accompanied by an obligation to bear responsibility. This is a particularly significant detail to be constantly reminded of each other!

Forming the cognitive system (see 8) begins even before a person is born. The most important concepts, such as “I,” “we,” “prohibited,” and “need” are formed by the age of three, and later they are quite difficult to change. Adequately forming the concept of “I” is a prerequisite for forming “we” (family, community). In turn, the “we” serves as a prerequisite for the formation of loyalty and identity (a sense of belonging to a group, nationality, etc.) (see Figure 5.1.1.).

Time is an irreplaceable and irreversible resource and, at the same time, a condition for the use of various types of resources. Therefore, time must be cherished and valued. Stealing someone else’s and your own time is a crime. If not prevented, wasting time in meaningless meetings, stealing time by giving out pointless tasks, polluting time with nonsense, and procrastinating on decisions can become a form of destroying life. Even entertainment, if it becomes an end in itself, can have a devastating effect.

RIGHTS, OBLIGATIONS, AND RESPONSIBILITIES

Rights, obligations, and responsibilities operate together and are interrelated. If any of these links are missing or unclear, then any system will inevitably start or continue to decline.

A sense of responsibility can develop among those who have a real opportunity to participate in the decision-making process themselves. This is how all spheres of life and levels of regulation are arranged (see 7.2.1.).

- A sense of responsibility and activity are formed — together and at the same time — in the process of independent decisions.

- Participating in the game version of decisions generates neglect and causes alienation (see 3.3.) or causes a sense of inconsistency in cognition (cognitive dissonance, see 2.5.).

Based on this knowledge, it is easy to understand why some people are passive, indifferent, irresponsible, or, on the contrary, aggressive and reckless.

- Many fear freedom because freedom is accompanied by the right to decide and the obligation to be responsible.

- Freedom comes with the need to be accountable also for what should have been done, but nevertheless was not done.

RESPONSIBLE ACTIVITY

In order to act responsibly, a citizen needs to:

- be sufficiently informed about what one needs to be informed about;

- be experienced enough to anticipate and be aware of both the good and the necessary, as well as the harmful, the bad, and the dangerous;

- be sufficiently educated to understand in what field one has sufficient information, experience, and education;

- be honest enough not to participate in decision-making procedures when one is not willing to take responsibility and does not know of alternative opportunities;

- not pass off opinions, dreams, speculations, etc. for real knowledge and skills (see 2.8.).

What do people do to avoid responsibility?

- They strive to arrange themselves so that they do not have the rights and responsibilities that imply independence of decisions.

- They deliberately leave themselves without the necessary information for decisions, do not rush to participate in discussions and express their opinion, later taking the position of “I know nothing, I have not seen or heard anything.”

Activities also require:

- quite a lot of moral and formal rights, coupled with good faith, which allows these rights to be enjoyed fairly;

- quite a lot of moral and formal obligations, coupled with a sense of duty, forcing one to carefully fulfill these obligations;

- a sufficiently clear understanding of one’s own formal and moral responsibilities so as not to forget or fail to fulfill one’s obligations;

- dignity, so as not to act as an expert in areas that are still not clear;

- faith in the Creator, in yourself, in your abilities and the abilities of others, in success, in the future;

- will, perseverance, consistency, courage, and caution to condemn both recklessness and cowardice;

- good relationships based on sincerity, kindness, honesty, caring, generosity, openness, trust, respect, love.

Types of responsibility:

- Human responsibility, defined and limited by being human;

- Responsibility due to culture, adherence to culturally fixed values and norms, virtues, myths, and taboos (see, for example, the Ten Commandments);

- Responsibility associated with specialty, profession, occupation (position), role, and status;

- Legal responsibility related to the legal norms in force in the society.

Note here that a sense of responsibility is formed in the process of independent decisions; at the same time, shame accompanies both evading decisions and participating in decision-making with insufficient knowledge of their essence.

In addition, a unity of social and cultural ties is necessary, through which it would be possible to highlight:

- right and wrong aims and goals;

- appropriate and inappropriate means;

- moral and immoral principles and evaluation criteria.

It is necessary:

- to be able to distinguish between noble and degrading, worthy and unworthy, caring and indifferent action and condition;

- to make sense of your own activities and those of others, providing them with goal visualization and feedback (see 6.2.);

- to be so consistent and persistent that, despite the difficulties, one is able to bring what has been started to the end; the latter is justified only if it is clear that this activity is expedient, sufficiently effective and intensive, and is not conducted at the expense of people, nature, or culture.

A normal citizen tries to be knowledgeable in many areas (see also 1.7.), at least enough to understand what he needs to research, study, try out and practice before taking any (senior) position and teaching others, giving to and assessing others, writing programs and projects, etc.

It is necessary to be selfcritical and continuously improve yourself, keeping in mind that all people have their own characteristics, and they are all worthy of admiration and attention.

To be happy and content, you need to have a circle of companionship that is worthy of a place in your heart, cherished and protected, but still remain free and independent enough. A prisoner can do something too, but if he must (is required to) do what is ordered, as ordered, when ordered, where ordered, from what is given, here, now, to a specific deadline, etc., then he cannot be held responsible for the results and consequences of his activities. A prisoner seeks freedom, a slave wants to become a slave owner. The only thing worse than a slave spirit is indifference.

YOU CAN’T MAKE ANYONE HAPPY

In order for a person to feel happy, it is necessary that they:

- were healthy and could take care of the health of others;

- could believe and trust other people, including teachers and managers;

- had information about both the present and the past;

- had an idea of the future;

- understood why something was being talked about and something was

- being silenced, and why something was being done and something left undone;

- was able to anticipate the results and consequences of both changes and preservations;

- could (would be able to, had the right to, dared to) participate in the discussion, express an opinion, ask questions and clarify, supplement, and doubt until it can be verified;

- felt needed;

- received a decent payment for their contribution;

- was protected from all sorts of deceivers and other intruders;

- recognized the causes of good and bad;

- could take care of, protect, and love their children, parents, and spouse and feel secure, protected, and loved at the same time.

- You can’t make anyone happy; you can try to arrange life in such a way that everyone could be happy.

- No one can be happy sur-rounded by unhappy people!

YOU CAN’T MAKE ANYONE SMART

The greatest value is the cognition that forms in a person’s head as a common space, the intersection of three domains: the psyche of the person themself, as well as the person in their micro- and macro-connections. No one can put this common part into the head of another, give or donate it, but it can be formed in those who are able to master the basics of psychology, social psychology, and sociology (see 0.3.). Mental processes, states, and phenomena, as well as human relations and interaction in the micro- and macro-environment, can be described separately, but in order to navigate society and culture, it is necessary to understand the common space of these three scientific areas (see Figure 0.3.5.).

To facilitate analysis of the assumptions and results of one’s own life and the lives of others, models can be helpful (see 7.3. and Figures 9.3.1.; 11.1.11.). At the same time, the very process of comprehension using these models can initially cause difficulties — practice shows that it will improve gradually.

NB! Theories are valued only by those with developed skills and holistic thinking patterns. The theory is useful for practice only if it is mastered together with the methodology and methods.(see 8.3.). Single fragments gathered here and there will not form a clear and reassuring view that encourages independent reflection (thinking) and action.

In a society where people are left without the necessary training to navigate it, the citizenry (the very people who are the bearers of supreme power) cannot enjoy civil rights and perform their civic duty, let alone bear responsibility.

A person can become educated only by themself and only if an epiphany, a miracle, occurs in their head (and heart!) and they manage to understand what makes such a miracle possible.

You can study texts. Knowledge is accumulated in the process of studying. However, the unity of knowledge, skills, and understanding is needed. Skill is formed through exercises and experiments, understanding arises through reflection and comprehension. Something can be understood by teaching and explaining to others. It is especially good for those who are lucky enough to prove the integrity of their knowledge and mastery of the subject to their teacher-instructor. However, nothing much will come out of answering an exam or teaching others if the knowledge in your own head is not ordered, not systematized, and not meaningful. If the knowledge and skills can be applied to the next level of systems, it is possible to grasp their importance and meaning (see Figure 9.1.5.).

A person can become educated only by themself and only if an epiphany, a miracle, occurs in their head (and heart!) and they manage to understand what makes such a miracle possible.

It is worth considering why it is the case that only those who have done empirical scientific research are suitable for teaching at a university (in academic institutions where teaching is also conducted); in other words, those who have formulated a problem and established a number of reliable facts in connection with it, compiled an impeccable explanation of their research (dissertation), and defended it in public debates (see 8.2.).

You can master your subject with the help of literature and observations, but in order to transfer knowledge at a university at the required level, you yourself should go through all the stages of scientific research; that is, learn from your own experience how to obtain statistical facts from empirical facts and derive scientific facts from them.

Scientific inquiry results in an understanding of the environment and its functioning, the human being and the functioning of the human community, an understanding of the importance and significance of the laws of society, nature, and logic. Someone who has successfully passed through all this has a potential that students pick up instantly. Such a person (see 1.7.) develops a professional style, a special mindset. An adequate professional treats other professionals with emphatic respect, and behaves in a demanding, approving, and inspiring manner towards them. A professional is reliable and creates a sense of confidence in their environment. Remember that professional communication is only possible in a circle of people of the same level; a substantive conversation will not work with those who are not competent in the field — a professional can only talk to them on abstract topics.

COMPETENCY AND QUALITY DECISIONS

The position of a manager at any level, which implies the right to decide and the obligation to bear responsibility, is not a privilege, but an opportunity to serve other people, one’s country and nation.

A doctor is a good example. It is considered normal that in order to become a doctor, you must begin your studies with anatomy, physiology, histology (see 2.4.) and, upon graduation, have a clear idea of what constitutes a healthy person. No one asks a doctor if she knows where an organ is or what, in her opinion, is the purpose of this or that organ. She must know all this with impeccable accuracy, must be able to convey the information to her colleagues in competent Latin so that all possible errors are excluded. As for physicians who are allowed to practice independently after a dozen years of study, everyone unanimously takes it for granted that they must be competent by this time. There is a perception in many fields that it is not appropriate to demand competency from decision makers. There is a perception that a quality decision can be formed without proper training. In some sectors, they even went so far as to say that the less knowledgeable a person is, the better. Under an incompetent manager, people feel like a patient on the operating table who is being operated on by a “doctor” who has only seen a scalpel in a picture.

UNJUSTIFIED AUTHORITY

The administrative position is accompanied by the right to make decisions that affect the lives of other people (permission-prohibition-order, praise-reprimand and punishment, hiring and appointment, promotion and dismissal). People who have unjustifiably come to power (see also 11.1.) behave in a similar way. They try to immediately hide their identity, activities, and results. The better this is done, the more intensively bureaucracy spreads (see 12.3.): specialists are either laid off or forced to remain silent, generalists (see 1.7.) are ridiculed, colleagues are treated as objects of manipulation. Those who dare ask anything about the expediency and effectiveness of the activities are answered with a sneer like, “What’s it to you? Mind your own business.” Regarding the results, they say: “Those who need to know, know and are able to give an assessment.”

Lying and embellishing reality become the norm. To justify the actions of the authorities, to conceal facts, and to write “responses” to letters from citizens, “public relations specialists” are appointed to a special position. Meaningful office work and well-reasoned explanations are replaced by propaganda phrases coupled with empty promises to “increase”, “strengthen”, “expand”, “deepen” and “accelerate.”

When citizens in the state and personnel in the enterprise or organization do not have the opportunity to be informed, the estrangement increases (see 3.3.) especially among educated and experienced professionals. Bureaucracy plays the same role in society as cancer does in the body (see 12.3.). Just as it is possible to escape the claws of cancer only through fairly radical methods, citizens can only get rid of bureaucracy by speaking out strongly against it and eliminating the causes of it.

- Society can develop satisfactorily only if the principle of competency is followed at all levels of regulation and management.

- The power of those with unjustified authority is a source of both material and spiritual poverty.

Individuals with unjustified authority come to power and remain in power with the support of lackeys and deception, clearing the way for each other, keeping their own and others’ secrets.

Here is an example of one of the consequences of “elections”: individuals who do not have the necessary qualities for responsible activity, but who get onto decision-making councils, choose from among their ranks exactly the same kind officials, who in turn choose similar advisors, and so on.

There are two possible outcomes:

- either the bureaucracy will destroy the state, and the citizenry will give up (“nothing depends on me, and there’s no point in trying hard, because sticks alone without a drum can’t do anything”)

- or the citizens will get together and break the bureaucracy without fear or whining. To do this, you must be honest, professional, selfless, and consistent. A citizen who respects and loves their homeland is capable of this.

SOCIETY AND CHANGES

In society it is impossible to behave in the same way as in a material environment. In a material environment, you can rearrange objects, cut, chop, drill, file to size, mill, chisel, etc. In relation to people and society, you cannot behave like that. Human attitudes and relationships are shaped by direct or indirect contemplation and are manifested in the form of assessments, conclusions, motivation, and orientation.

In order to cause any changes in the behavior of a person or a set of people, it is possible to:

- resort to administrative measures (orders, prohibitions, punishments, and other forms of violence); however, it is impossible to achieve something worthy by unworthy means;

- arouse interest, need, increase motivation, change relationships and structure (position relative to each other), strengthen desire, faith, hope and love;

- change the factors of activity in order to cause a change in the next step, after the necessary time has elapsed.

NB! Something could be changed in society and its subsystems only if and only when it is understood exactly what cannot be changed; that is, what should be protected and defended. Hence the conclusion: when formulating various programs and setting aims and goals, it is first necessary to clearly articulate in writing, as well as publicize, what needs to be preserved and how this preservation will be ensured. Only then can we determine what should be changed; how to act appropriately so that the necessary change happens quickly enough and takes hold; and who is responsible and accountable (when and where!) to the public for the results and consequences.

It is impossible to achieve anything worthy by unworthy means.

For a citizen to serve satisfactorily as an official of a state or municipal institution, it is not enough to be familiar with finance (or economics), law, politics, and ideology!

It is necessary:

- to know and understand the individuals and sets of people in social, cultural, familial, and community relationships;

- to have knowledge of targeted systems and goal-oriented processes;

- to understand the prerequisites for management, work (execution), and self-regulation;

- to understand that rights to decide come with responsibility; • to recognize that lying and kowtowing is in poor taste.

CREATING SOMETHING NEW IS A BRAVE THING TO DO

Creating something new is always courageous. An innovator must either deny the old, claim to interpret something completely new, or look at something in a completely new way (see Figure 2.8.1.). Most innovations are a response to those who have previously been involved in the field. It is especially difficult (sometimes impossible) to change the interpretation of any field as a whole — in such cases, we are dealing with a paradigm shift (a holistic semantic structure). For example, the soviet planned economy represented one paradigm and the market economy represents a completely different paradigm [1].

All factors and their interactions must be considered when creating something. No single factor alone can be strong enough to lead to success. At the same time, each factor is so powerful that ignoring it can lead to failure. To destroy a well-functioning system, it is enough to destroy several or even one factor. In contrast, creation is a much more complex process.

Engineers, chemists, and physicists (as opposed to “ordinary” intelligent people) may find it difficult to understand that the laws applicable in the material world are not valid in the social and social spheres. For example, it is impossible to increase the birth rate or reduce emigration through orders and slogans. Population-related processes could only be influenced by changing their factors.

To regulate emigration, one must know (not assume or suppose, but know!) why people choose to live in their homeland, despite the difficulties, and what makes them decide to move elsewhere.

To understand why children are the greatest joy for some people and why some people do not invite the stork to visit them, it is necessary to know the life and living environment, communication and the impact of communication, and why deception and lies, indifference and meanness are not acceptable to everyone to the same degree.

Finding one factor is not enough! You should know the system of factors. We need to consider what people’s sense of confidence, faith, and trust are; what is their hope for coping in a situation where wages are laughable and improving living standards is apparently not expected.

The law of the barrel or anchor chain:

- none of the barrel boards can be more important than the other — if even one board is missing or broken, there is no barrel per se;

- all the links of the anchor chain are equally important — if at least one of the links has degraded, the whole chain is unfit.

Our ancestors already knew that none of the boards of the barrel can be more important than the other — if at least one board is missing or broken, then it doesn’t matter how good the other boards are: the barrel simply does not exist anymore. This so-called law of the barrel or anchor chain [2] is universal and suitable for use in any area of life and at all levels of management (see 7.2.). Similarly, it makes no sense to talk about one single, most important element in social regulation — all of them are important.

Instead of talking about the system, you should take a pencil and draw on paper the system in focus as a phenomenon and as a process. Then you can record the actual and desired situation, discover the reasons for the contradictions between them, and figure out what can be done about those reasons.

[1] If the reader has deeper interest in the field of paradigm, the suggestion is to study texts created by American philosopher Thomas Samuel Kuhn.

[2] In case you are deeply interested, it is worth reading Ludwig von Bertalanffy’s concept of a general systems theory.

1.1. MORALITY

Success in social and cultural regulations, management, governance, administration, in any directed and goal-oriented activity can, in principle, be achieved:

- at the expense of people, nature, and culture, or

- in harmony and respect to people, nature, and culture, as well as a system of moral concepts.

Morality as the basis of moral behavior is a function of culture (see Figure 5.3.1.), which has evolved over the centuries through generational succession and regulating human attitudes and relationships, intercommunications, thoughts and behavior.

What is moral is that which is in harmony with the norms of morality and values developed over time.

Anything that is in conflict with moral norms, values, and virtues is considered immoral.

Relationships in which moral issues are ignored and ridiculed are called immoral.

The field of philosophy or teaching with morality at its center is called ethics. A person who has grown up among cultural ties has enough intuition to make a moral choice. Nevertheless, there are situations in which, before acting, you must stop and realize that you will be responsible for your actions sooner or later, either administratively or morally, or perhaps both, here and now or later. Every step that matters to other people, nature, and culture must be justified at least for yourself and make sure that there is a fairly holistic and reliable view about it. If your conscience leads you forward, it is not difficult to find the right path without outside help and influence.

UNIVERSAL, NATIONAL, LOCAL

In every culture, we can distinguish universal, national, and local norms of morality. Difficulties begin when these three components do not fit together, or if the people living next to each other have radically different norms of morality, values, myths, and taboos. Universal human morality is more stable, while national and local morality is more labile (variable).

It is natural and self-evident for every citizen to follow the norms of morality. A person who does not respect the norms of moral behavior does not, in fact, respect other people as well as their own culture and society. Immoral behavior is a sign of disability.

Society cannot exist for a long time without culture (morals, customs-rituals-traditions, language and attitudes, faith, honor and respect, dignity and shame; see also 5). Everything that forms the culture (the foundation of the nation), helps to preserve and strengthen it, should be mandatorily preserved, protected, and defended. If an action could in any way harm the culture (have a negative effect on it), it is wise to stop it as soon as possible. No one has the moral right to harm culture.

- Morals are morality, ethics.

- Morality is respect for moral principles and rules, recognition of established norms and values.

- Amorality is ignoring accepted moral rules and principles, following principles that contradict them.

- Immorality is non-recognition, exclusion of morality.

- Ethics is the science of mora- lity, a field of philosophy that studies values and norms, myths, taboos, and virtues.

- Moral behavior is ethical behavior; the practice of values and norms in dealing with and treating others, developed in a particular place and time.

- The functions of ethics are the phenomena and processes that objectively accompany respect for ethical principles (humanity, confidence, love, faith, loyalty, faithfulness, courage, moderation, etc.)

The peculiarity of morality in comparison with other phenomena of social life is its all-pervasive ability. Morality runs through all human acts in all spheres and at all levels of regulation and guidance (see Figure 7.2.1.).

Morality protects and reinforces the established order, while being the most revolutionary component of philosophy. Morality enhances or restrains individual freedom. Morality can unite people, give value to their future, reveal the meaning of life and existence, call for rebirth, save them from degeneration, convince them of their own rightness, or destroy them with a ruthless sense of guilt.

THE BASIS OF SELF-REGULATION

The primary basis for the actualization of moral issues is a person’s daily behavior, communication, and relationships. They can be humane or inhumane, tolerant or hostile, respectful or humiliating, based on the recognition of free will or coercive; they can be cordial, can appreciate or ignore an attempt at mutual understanding. In the sphere of actualizing morality are also, for example, the self-interests of the individual. Pursuing personal gain and prioritizing personal interests sooner or later leads to such internal or external tensions that productive activity is simply impossible. Left unchecked and without reaction, small deceptions and thefts, due to cognitive dissonance (see 2.5.), seem to encourage larger abuses, and after a few years, deception and theft become a lifestyle, which the cheater themself calls entrepreneurship.

Stealing and cheating are not only about things and money, but also about time and space, energy, knowledge, attention, rights, benefits, etc. Any speech justifying such activity is immoral.

Primary is self-regulation, which is based on morality — not orders and prohibitions, but human conscience, love, caring, etc.

For violating moral standards, fines or other penalties are seldom imposed, and a person is rarely fired or imprisoned. People simply stop communicating with those who have fallen morally. Divorce is not uncommon. Tension can only be relieved through a sincere admission of guilt and apologies. The offender must clearly articulate that their act was unacceptable. They must promise that they will not do this in the future. If the request for forgiveness and the promise are sincere, it is reasonable to forgive them.

If forgiveness does not follow, then there is a high probability that in the future the wrongdoer will not tell the truth and admit what they have done, and each further failure will spoil the person even more, because in order to continue to exist (restore the balance of mind) the immoral person must convince themself and others that they did nothing wrong, and that what they have done is right. Alternatively, they might try to escape from reality and bury themself under a pile of other things.

1.2. THE PERSON AS AN INDIVIDUAL

The individual or person is a living system, different from others and related to others in inexpressibly complex ways. This characteristic is commonly referred to as personality. Each person lives in their own time and in their own space, or more precisely, in their own spacetime continuum, in their own system of connections and dependencies. What will come out of life, what trace will be left in it, and what will be the arc of life depends on the degree of enlightenment, health, character, temperament, as well as the stage of development, which has its intellectual and emotional, physical and spiritual, social and moral components.

Each person has individual characteristics and interrelationships with other people. The meaning and significance of the individual are shaped in the context of the next level of systems. The individual has multiple meanings, formed in different metasystems and manifested depending on where (in which metasystems) the person functions. The same events and stages of life can have many different, and at the same time correct descriptions coupled with different, including contradictory, assessments. It all depends on the context in which and with what intention one tries to interpret an individual’s activities.

The individual is characterized by:

- Questionnaire data: age, sex, weight, height, marital status, etc.

- Individuality: distinctiveness, originality, identity; what makes them different from others, what makes them stand out, what attracts attention. Individuality manifests itself through character, disposition of life, complexes, phobias, pathic ties (sensory ties), habits, customs, etc.

Individual characteristics may be innate or formed over time. The individual belongs to a nation, and his or her sexual traits may highlight, for example, different degrees of masculinity or femininity, orientation, etc. They are also characterized by belonging to a group, relationships, roles, and status in each role. The stratification index (the position of an individual in the social hierarchy, characterized by the quality of life and position in the social and cultural regulation (see 2.6.) can act as an integrated index.

1.3. PERSONALITY, MEMBER OF SOCIETY, AND REPRESENTATIVE OF CULTURE

Personality, as has already been said, is a person’s social quality. Personality characteristics, for example, are a sense of responsibility and a sense of duty, industriousness, a sense of right and justice, and:

- The degree of self-sufficiency is independence (in relation to what and because of what), as well as what order means and why order is necessary; what and how you can adjust to yourself, and what or whom you need to adjust to; why it’s not allowed to be and you cannot be completely independent.

- The degree of freedom is freedom from something and for something, as well as an understanding of where the boundary lies between them and what the measure is; what happens when the limit is reached and the measure is overflowing, and why it is no longer allowed or possible to be free.

In order for a person to behave as an individual — to think, speak, and act self-sufficiently — they must be sufficiently free and feel themself in a situation of choice as a subject.

It is not difficult for people who have realized themselves as citizens to understand that all members of society have equal rights. All rights can be enjoyed to the extent that they do not violate the same rights of others and the living environment in every sense of the word.

Self-sufficiency means independence — no dependence on other people. What is absolutely clear is that great success can only be achieved through cooperation, and people are in principle interdependent on each other. The question is whether this dependence is supportive, uplifting and inspiring, or oppressive and overwhelming; episodic or permanent; whether it manifests itself only in details or in everything, being, in principle, a whole; whether it is overt or covert, etc.

- Paradox is a truth that appears to be a lie.

- Demagogy is a lie that appears to be true.

Freedom is an ideal, a lofty idea, a dream for which people fight at all times, give their lives, and overcome all kinds of difficulties. And at the same time, it is difficult to find something that people fear even more than freedom. Freedom comes with the right to decide, and decisions come with the obligation to be responsible.

If responsibility seems to a person too heavy a burden, then they tend to do everything not to have the right to decide, but simply to observe everything that happens from the sidelines. This is the real paradox.

What do freedom and independence depend on? It’s not just about physical barriers, but above all intellectual, emotional, and moral ones. Only someone sufficiently educated, informed, and experienced to think independently can be free. For example, tuition fees are a payment for future freedom — by learning, it is possible to achieve readiness for independent orientation, thinking, decisions, their implementation and assessment; the ability to live your own mind and create the conditions for others to succeed. That is, education creates the prerequisites for a free life.

The individual, as a person, is a member of society and a representative of culture. They can behave as a representative of society if they have the authority to do so. A person is a representative of cultural ties everywhere, both at home and in foreign lands, at every moment of their life. In order to be free and participate in shaping decisions, a person must have both a formal and a moral right.

THE NEED TO BE EDUCATED, INFORMED, EXPERIENCED

The citizen understands and takes into account that every right is accompanied by obligations and responsibilities. This connection is fundamental. For example, if someone is elected to parliament or to any other deliberative body, this is accompanied by a formal right to participate in the activities of the relevant council. However, those who have no idea what needs to be done and what should be sought to be achieved have no moral right to touch the voting button. This applies to any board, any position, even home life. When discussing a budget, it is important to see the whole and to be able to foresee what society would become if the proportions and priorities of the budget were just so.

It must be remembered that it is not parliament or other councils that act — it is people who act. It’s not the board that decides, but the board members. It is not the government that decides, but the ministers along with the prime minister. The decisions approved and passed by a government meeting are, for the most part, compromises with which virtually everyone around the table must agree, given that these decisions contain only a fraction of the proposals originally submitted.

The law does nothing and is not responsible for anything. The people who drafted and approved this law are the ones who do and are responsible. The factory does not work, but the people working in the factory do, etc. These and other similar clarifications may seem unimportant, but upon closer examination we can see that the techniques of concealing the mechanism of responsibility are the cornerstone of demagogy (see 12.3.).

It may not seem like there’s a problem with someone speaking a little incorrectly. The main thing is that everyone understands. With regard to the examples cited, the point is precisely that with vague wording it is impossible to understand what is being said correctly, because the person answering is hidden behind circular phrases in the style of “a proposal has been made.” If you think correctly, then why express yourself incorrectly? If the life of the state and people depends on the activity, then there is no need to talk in vain. A person should speak clearly enough so that there is no misunderstanding.

THE NEED TO BE RESPONSIBLE

As mentioned above, a sense of responsibility and activity are formed only in the process of independent decisions, and decisions are possible only in a situation of choice.

Any attempt to decide turns into a game or absurdity if, instead of a situation of choice, a person finds themself in a situation of coercion. To avoid major trouble in such cases, people pretend not to understand what is going on. They play along, knowing full well that the main rules of this game prescribe showing genuine sincerity and seriousness. If an employee in a managerial position does not have the conditions for meaningful, moral, and correct conduct of business, and if in their arsenal there is force, coercion, absurdity, games, and demagoguery, then this state of affairs should be considered immoral.

THE NEED TO PRESERVE MORALITY

A lack of culture and disregard for cultural norms, values, and taboos inevitably accompany immorality and amorality.

A lack of culture also goes hand-in-hand with the bosses’ hope to achieve highly moral (disciplined) behavior in their subordinates through directive methods. Because of a lack of culture, an illusion grows that the stricter the order that is introduced and the harsher the penalties imposed for violations of legal norms, the fewer such violations occur and the more moral society is.

A moral personality in an amoral environment (B) can turn into a being who does not care what others do or what the results of their activities are. They may also become a dissident, actively fighting for the recognition of morality and morality as a value, opposing amorality both in their living environment and in the living environment of others, in the hope of transforming it into a moral environment, that is, suitable for life, for both present and future generations (A).

An amoral personality in an amoral environment may feel like a winner for a short time, but society will perish under this state of affairs (D).

A good piece of advice that can be given to an immoral or amoral executive (see 11.1.) who thinks that their authority has nothing to do with lying: go far away and get a job where no one knows you and no one you know is dependent on you anymore. And if you stayed in your place, you could have fixed something with sincere regret and apology.

1.4. A PERSON AS A SUBJECT

The subject can be a person or a set of people who are an active actor. In sociology and social psychology, the subject is seen as the initiator, implementer, linker, and responsible for a goal-oriented, aimful activity.

If the focus of the subject is on the processes through which they want to achieve (must achieve) customer value results, streamline the environment, or provide services, then it is about management and execution (work).

Upbringing is the creation and preservation of an environment favorable to human growth and development.

An activity in which the subject self-asserts and acts in the name of achieving order and respect for order (subordination) is called governance (domination). Sometimes they try to think of it as upbringing. Just in case, let’s reiterate that according to the interpretations presented in this book, upbringing is the creation and preservation of an environment favorable to human growth and development (see also 2.2., 2.8.).

What characterizes the subject? (See Figure 1.4.1.)

Cognition. Self-knowledge, group cognition, social cognition, cultural cognition.

Consciousness. Formed in accordance with cognition. Selfconsciousness (“I” feeling) is formed according to self-knowledge; group consciousness (“we” feeling) is formed according to group cognition; social consciousness or civic feeling is formed according to group cognition, and cultural consciousness or identity is formed thanks to cultural cognition.

None of them can be formed by force. It is only possible to create the necessary prerequisites for their formation by creating the right conditions and a growth-enhancing environment (cognitive system factors). Self-knowledge, as well as group, social, and cultural cognition and the corresponding consciousness, are the foundation of a citizen’s education and life.

Preparedness. Preparedness is needed for orientation, decisions, executing decisions, and linking implementers, for assessing activities and results, and for making adjustments when necessary. It is essential that learning, upbringing, and experience enable a person to form a patriotic personality with a desire to actively serve their country and nation.

The Constitution speaks of the right to education, but does not speak of the right to be informed. Along with commercial broadcasting, there is also national television and radio broadcasting, but for some reason its management considers that its duty is to broadcast entertainment programs, rather than to ensure that the public is informed about everything they need to know for a citizen who wants to participate in public and cultural life.

A partially informed person feels cheated or rejected.

Adequacy and correspondence to reality are central to both cognition and consciousness. If a person sees themself and others in a distorted mirror or if, because of poor and non-systemic education, their mind is confused and they can see only some parts of the whole, and even these parts appear distorted and unrelated to each other, then in this situation the formation of an adequate “we” is virtually impossible.

1.5. ROLES AND STATUS

Each person has a large set of roles — all of life is spent in some roles, and each of us can be seen as a set of these roles. The more roles a person has, and the more roles the people around them know, the more likely the person is to be successful in life. Practicing in roles and role changes

begin in early childhood, when the child in the course of a game is a locomotive driver, then a passenger, then a ticket inspector, then a station master, etc.

The Key to Happiness:

- For a person to be happy in their role, they must do everything possible so that the one who has the opposite role can also be in their role.

Adequate understanding of roles, an awareness of one’s place among various connections and situations can be formed only in the context of culture, through direct and mediated experience.

Language is necessary for communication, but it is not in itself a sufficient prerequisite for a person’s ability to communicate in their cultural space — language does not communicate. The value is the unity of language and attitudes — it is necessary to master roles and behavioral stereotypes as the foundations of culture, to assimilate them and accept them (interiorize).

In any role, it is wise to consider:

- Accuracy. Mastering a role, i.e. getting answers to the questions: “What did I get myself into?”, “What is going on here?”, “How am I supposed to behave here?” is an important part of the socialization process (see 2.2.) You can behave in a certain way only within a role;

- Cultural Stereotypes. In order to succeed in a foreign country, one must understand the local cultural context and behave in accordance with it. “When in Rome, do as the Romans do;”

- Status. Being in a role, a person has a certain status in the eyes of others. Incompetence, lying, deceit, betrayal, and unworthy behavior diminish status. Behavior that meets or exceeds expectations raises status;

- Authority is a set of statuses;

- Roles should be changed quickly and easily. A person stuck in a role can become unbearable and annoying to others. For example, a person frozen in the role of a teacher, who remains a teacher at home, at work, among friends;

- You should be in your own (!) role. A person eager to be in the role of others generates contradictions that can escalate into conflicts. It’s important to think about when and what roles to live in, and what roles to avoid, whether at home, at work, or somewhere else.

- To be (behave) in a role is possible only if there is someone in the opposite role. The opposite role should be known, as only someone who has created all the conditions for people in the opposite role can be happy in their role. Any manager can be in their role, as long as they understand the roles of their colleagues. Examples of opposing roles are: teacher and student, seller and buyer, doctor and patient; in the family, wife and husband, children and parents.

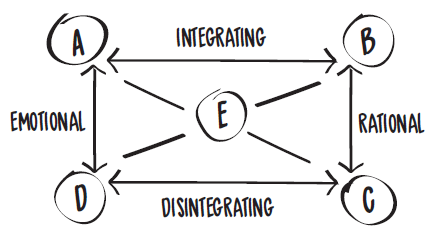

An emotional integrator (A) can function and feel as necessary as someone who is a rational disintegrator with the same clear organization. It makes sense to be in the role of a rational integrator (B) if someone is in the role of the same emotional disintegrator. An emotional disintegrator (D) and a rational disintegrator (C) are also necessary. In Estonian culture these roles in the family are often distributed as follows: A — mother, C — father, D — mother-in-law, B — father-in-law. E are children who integrate or disintegrate on both a rational and emotional level.

Any person in life has a role as both a decision maker and performer. In both the decision and its execution, it is important to understand your role and create the necessary conditions for the opposing party. A person is happy when surrounded by happy people. Each person is the blacksmith of their own happiness insofar as they have succeeded in creating the conditions for the happiness of others.

- A person in any of the roles has a certain status in the eyes of those people who are exposed to the roles.

- Authority is a set of statuses.

1.6. PERSON AS A CITIZEN

In a legal sense, all people living in a country and holding citizenship are citizens. Among those who live in Estonia and do not have Estonian citizenship, a large proportion are citizens of other countries. Regardless of citizenship, everyone has equal human rights. It is assumed that in a knowledge-based society, all people want to participate in the choices they make; all are loyal, honest, and professional enough to behave conscientiously and responsibly in the context of social and cultural connections. In reality, this is not the case.

There are quite a few prerequisites for being a citizen and behaving in social and cultural life in accordance with the knowledge received, conscientiously and responsibly. These prerequisites do not form on their own, by chance. In a democratic society, these preconditions must be created, preserved, and considered.

WHO CAN CONSIDER THEMSELVES A CITIZEN?

A person can consider themself a citizen if they:

- know what is done and how it is done or left undone;

- want to know why something is done or not done, what depends on what is done and not done, and what, in turn, depends on the people who are active and their activity, as well as the results and consequences;

- care about the unconditional and systemic relationship between rights, obligations, and responsibilities;

- are not afraid to participate in discussions and decisions, as well as in the control over executing decisions (because they take into account that the obligation to be responsible is formed in this way);

- can be consistently demanding of themself and others;

- learn and want to participate in the lifelong learning process;

- agree to be nominated as a candidate for parliament, an official or councilor only if they are properly trained and personally prepared;

- understand the activity system, the cognition system, as well as the communication, financial, energy, transportation, and other systems necessary for orientation in social and cultural life (see Figure 4.0.3.);

- are able to view reality as a set of problems (see 0.3.);

- know how to identify and distinguish systems, analyze and generalize, isolate connections and dependencies, systematize and classify;

- require public disclosure, including public justification of decisions;

- despise secrecy and the use of all kinds of deceptive and coercive schemes;

- do not participate in procedures that are contrary to the Constitution or culturally established good traditions (intentions and mores);

- make every effort to protect and strengthen the constitutional order.

A sense of duty is formed in the process of upbringing, a sense of responsibility — in the process of independent decisions.

The key factor in public and cultural life is decisions, that is, the willingness of various categories of the population to take real, not fake, responsibility for what is happening in society and in culture.

The Constitution gives all citizens equal civil rights, but if no one is required to ensure that they can effectively exercise those rights, they become a fiction. The Stalinist Constitution in the USSR was particularly high-minded and astonishing. The day of its entry into force was a non-working day and should have been celebrated with a national celebration. At the same time, anyone who even hinted at the Constitution and the civil rights written therein was considered a dissident.

Whoever dares to look closely will notice that even today, those who have the power to decide often have no idea of the conditions under which the citizenry would be able to behave as subjects of self- and social governance. According to the Constitution, the bearer of supreme power in the state is (should be!) the citizenry. In reality, the citizenry have no right to influence what is happening in the country, i.e., to decide and demand that parliamentarians and officials take this decision into account, or at least organize a referendum, whose decisions would be obligatory for execution.

People who are left (abandoned) without the necessary conditions to function as citizens cannot exercise the (civil) rights established by the Constitution.

PREREQUISITES FOR THE FORMATION OF CIVIL SOCIETY

In order for society to become civil, it is necessary to create such preconditions in which all categories of the population (every person in the city and the village, in every sphere of life, in all agencies and at all levels of regulation) would have an opportunity to:

- be educated enough to understand what they should be informed about;

- be sufficiently informed to orient themself in space-time, in circumstances, positions, and processes;

- be experienced enough to anticipate and foresee possible changes, or the obvious results and consequences that accompany the lack of change, and to respond to them in a timely and appropriate manner.

Participation in decisions requires the ability to anticipate the possible outcomes and consequences of one’s own and others’ activities, including decisions and their execution, the reasons for successes and failures, and other connections.

CIVIC FEELINGS ARE FORMED IN PRACTICE

It is worth emphasizing again and again that the word “democracy” can easily become an empty sound. To maintain freedom and independence, everyone should always be on their guard and make an effort! Citizens will have a hard time if bureaucracy starts to proliferate. In this case, for most citizens, freedom will become a facade.

Freedom and independence sound good as lofty ideals. It is harder to understand that the preservation of ideals cannot be entrusted to someone else. Sometimes it happens that in the name of achieving an ideal, people are ready to go through any difficulties and self-denial, but when the ideal is achieved, there is no more strength or time to maintain it. Everyone seems to know that in the name of freedom and independence one must work constantly and purposefully, but when it turns out that to maintain a free and independent state one must reflect, learn, and continually improve, be knowledgeable and demanding, the gleam in many people’s eyes disappears.

One’s own state should not be a burden on a citizen! A citizen is a resident who wants to be a subject, because they orient themself not only to the good and the bad, but also to the factors behind these concepts. This allows the citizen to participate in decisions, connections, and execution, as well as adjustments if necessary. This is how participation, experience, and heartache arise, because along with real involvement (not playful or empty), an obligation to be responsible for the end result and for what awaits the individual, their state, and their citizenry in the future is formed by decisions and their execution.

Civic feeling is formed through practice.

NATION AS A COMMUNITY OF CITIZENS

A nation as a community of people can function as a subject (as an active source of responsibility) if it has an appropriate self-consciousness, group consciousness, social and cultural consciousness, and if it has both a state and national and local identity.

In order for the citizenry to conduct themselves as a subject, the following state of affairs is necessary:

- the citizenry have the opportunity to be sufficiently educated, informed, and experienced to navigate and deliberately participate in discussions, decisions, and assessment of outcomes;

- management is so honest, fair, and attentive that it responds to the wishes of the citizenry;

- mass media disseminates only reliable and systematic information, and the media form mass communication;

- elections meet constitutional requirements, random people have no chance of getting into parliament, local government, or any other decision-making assembly;

- the educational system provides satisfactory preparation for independent orientation in both social and cultural as well as community and family life;

- government decisions at all levels of regulation have goal visualization and feedback.

In order for a state to be and remain satisfactory, its inhabitants must behave like citizens!

1.7. PROFESSIONAL

At the level of domestic consciousness, each person can think as they please. Small decisions, the results and consequences of which have little impact on other people, can be made at your own discretion. If those elected and empowered at the official level begin to discuss and prepare such decisions, the execution of which can change the life and living conditions of many groups of people, nature, and the living environment, the situation takes on a qualitatively different meaning.

In the course of preparing serious responsible decisions, the execution of which is accompanied by quality transitions, it is necessary to try to be professional and moral.

- Profane. In most areas of life we are all profane, because we know nothing about them.

- Dilettante. In many areas we are amateurs, with a vague understanding and superficial skills.

- Specialist. We are specialists in some areas. A specialist is thoroughly and clearly oriented in a particular narrow area. A trustworthy specialist is one who knows what they don’t yet know, and what they won’t give an opinion about yet.

- Generalist. A generalist is a specialist in a field with the skills to encompass the whole — a system in a system of metasystems. A generalist is the creator of big decisions and involves quite a number of specialists in creating, executing, and assessing them.

How does professional thinking and conceptual thinking differ from that of an amateur or ignoramus? The answer could be short. Following the principles of this book, here we will try to simply present to you as many points of view on this concept (“professional”) as possible. Some of them will be discussed in more detail in the following chapters.

WORTHY PEOPLE ARE THOSE WHO:

- are guided by human virtues;

- are adequate;

- want to be professional (educated, informed, and experienced), despite the fact that the world around them is rapidly changing;

- think soberly and want to be at the forefront of progress;

- believe that professionalism is a prerequisite for success, greatness, and outstanding achievements, only if accompanied by human concern;

- understand that no subject can be fully learned, and try to use every moment to improve themselves.

A professional:

- uses words with a clear and definite meaning;

- finds quite a few points of view to consider the object of interpretation;

- takes into account that each point of view can provide an opportunity to see something that cannot be seen from another point of view, and knows that no single point of view can discern the whole (the system that is an abstraction for the observer, a mental generalization);